THE NEXT 50 YEARS: Richmond’s zoning overhaul envisions a denser city. What will that look like?

In the city of Richmond, few things provoke more feelings than a vacant lot.

3000 Q Street is no exception. Once a small, one-story shop, the narrow corner lot in North Church Hill now sits empty, a rectangle of grass that neighbors have come to view as an extra spot of green in the urban landscape.

All that will soon change. This March, Richmond’s Planning Commission and City Council signed off on a plan by Baker Development Resources to transform the lot into a three-unit apartment building. Each one-bedroom, 650 square foot unit is intended, said Baker planner Alessandro Ragazzi, “to provide attainable housing opportunities to individuals increasingly priced out of the market.”

The proposal sparked a backlash from many neighbors alarmed by a recent influx of construction in the area: a three-story, 13-unit development that houses popular eatery Soul N’ Vinegar on its first floor. Two duplexes. Two new single-family homes.

“The density of our block has greatly increased, which I understand is a good thing, but Church Hill is not downtown,” said T. Maxwell Shoup, who with his wife Alayna Craig owns the property next door. Besides worries about increased trash and less privacy, parking was a key concern, especially for elderly, long-time neighborhood residents who were finding themselves forced to park farther and farther from their doorstep.

“This effort to squeeze multiple residents into small spots is just getting exhausting for members of the community that are already here,” said another resident, Amy Ferry.

But for the Planning Commission, the project was a prime example of what Richmond needs. By offering both greater density and more housing, the proposal seemed to fit neatly into the vision of the city’s future laid out in its master plan — a document known as Richmond 300 that was the product of thousands of residents’ comments and years of labor.

“This is precisely what Richmond 300 is aiming at,” said Commission Chair Rodney Poole. “It’s going to be rezoned so that it will be more dense.”

The decision, and the conflict it sparked, is one likely to be repeated again and again in the coming months. Richmond officials and the public agree more affordable housing is critically needed in the city. Many also embrace the idea that a denser city is a healthier city, one with greater opportunities, more economic and cultural activity, less need to rely on cars, and, for a government that relies heavily on real estate taxes, the potential for greater revenues.

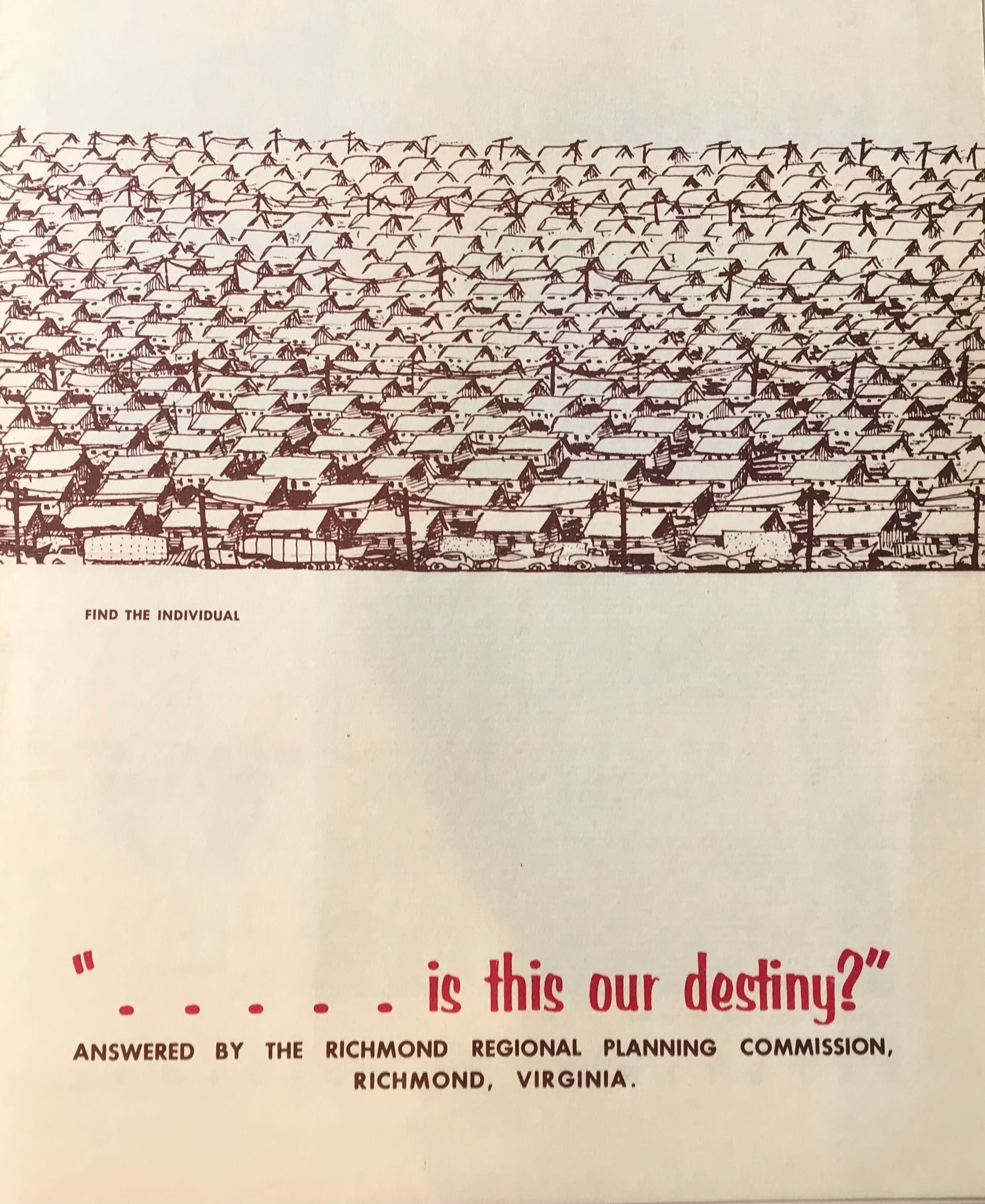

But while those ideas enjoy wide popularity in the abstract, feelings can get more complicated when the density moves in next door and residents feel its impacts in real time. It’s a possibility that many Richmonders will need to contemplate as the city overhauls its 1970s-era zoning code over the next year — a refresh aimed at not only encouraging greater density but also adapting the city’s land use rules to better reflect how people live in the early 21st century.

Richmond isn’t alone in its efforts: Chesterfield County too has undertaken a major overhaul of its zoning, which also dates back some 50 years.

“Most of this code that we have right now, this latest version, the bulk of it is majority-1970s, and it just doesn’t align with the economic, social, environmental realities of today,” said Richmond Planning Director Kevin Vonck.

So far, the Planning Department has rolled out potential new categories for zoning districts, potential new standards and what’s called a “pattern book,” a document that identifies the common elements of a neighborhood that give it its particular look and feel. Planners have organized panel discussions of the code refresh and are shopping it around for feedback at neighborhood association meetings, as well as soliciting the public’s thoughts through surveys and workshops.

The stickiest step is still to come. Citywide draft maps that will show how every address in Richmond could be zoned under the new code are expected to be released in May or June.

That, said Vonck, is “where we really need to have nuanced discussion.”

Officials acknowledge some pushback is likely. Residents in Oregon Hill have already complained about some of the city’s findings, including its determination that most of the structures in the historic neighborhood near VCU don’t conform with the current zoning code — a situation Vonck says is exactly the kind of problem the code refresh is designed to address. And the detailed maps are certain to trigger concern from at least some residents who live near transportation corridors where Richmond 300 envisions more multifamily development.

“I think people fear change, and the fear and uncertainty of ‘This is how my neighborhood has looked and felt, and now it’s going to change,’” said Elizabeth Hancock Greenfield, the vice president of government affairs at the Home Building Association of Richmond who also serves on the Planning Commission and chairs the city’s Code Refresh Zoning Advisory Council. But, she cautioned, “just because the zoning changes, it doesn’t mean your community is going to change overnight.”

Councilwoman Ellen Robertson, a proponent of the refresh who represents the city’s 6th District, stretching from Manchester in the south to Highland Park in the north, said it was important “to manage our expectations."

“Too drastic change will face opposition from people that are not comfortable with drastic change,” she continued. “I think the desire is to do drastic change, to significantly increase the zoning that allows more particularly multifamily housing, but I believe also that Richmond has such an entrenched history of such a large share of our land restricted to single-family housing that we may not accomplish the level of rezoning that I would like to see done.”

For Craig, one of the property owners next to 3000 Q Street, the fear is that in ushering in change, the city will fail to protect what is already flourishing.

“It’s so complex, because I understand what the city is trying to do for Richmond to help with our housing crisis, but I wish our city would be more thoughtful,” she said. “We do need more density, but it can’t come at the cost of established families and neighborhoods.”

A history of ‘excluding and welcoming’

The invisible hand that guides how a city grows or withers, zoning is always a fraught issue.

It determines where you can live and what kind of house you can build, where you can operate a business and what kind, whether you can have a driveway or a separate rental unit.