State health officials say Richmond water crisis was ‘completely avoidable’

Questions remain about delayed response to 2022 inspection

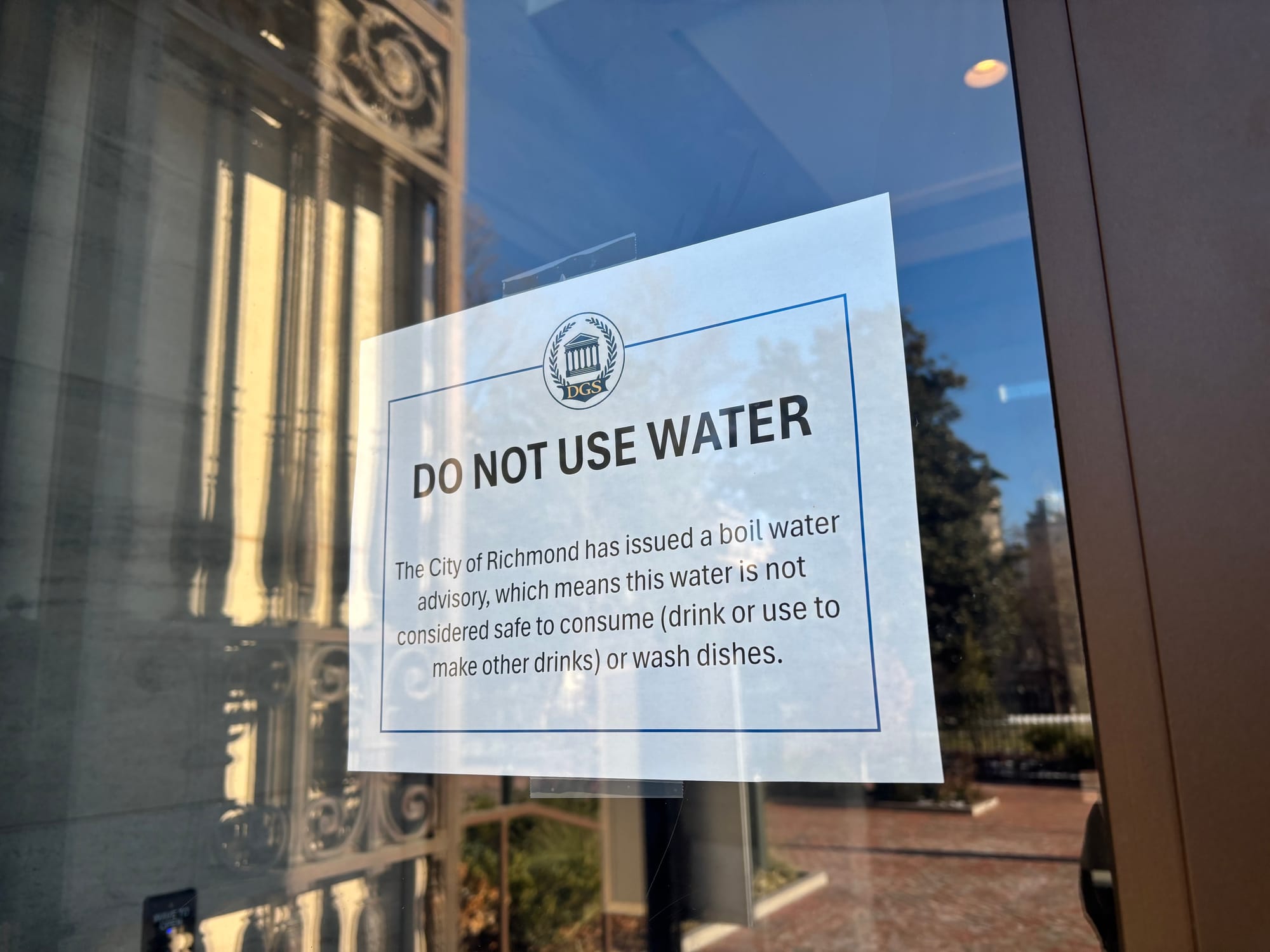

More than two weeks after a power outage set off a series of events that crippled Richmond’s water treatment plant, Virginia regulators are putting the city on notice that it may have violated state law and are launching their own investigation into what went wrong.

“The water crisis should never have happened and was completely avoidable,” wrote an official with the Virginia Department of Health’s Office of Drinking Water in a notice of alleged violation issued Thursday. “The City of Richmond could have prevented the crisis with better preparation.”

That preparation could have included “verifying critical equipment was functional before the storm event, ensuring sufficient staffing was physically present at the [water treatment plant] in the event of a power outage, and making sure staff present at the WTP during the storm event had appropriate training to effectively respond to the temporary power outage,” the notice continued.

The health department’s account of what happened at the plant, which supplies drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people in Richmond and its surrounding counties, largely follows what city officials have said: A Jan. 6 power outage required workers to manually switch the plant to draw electricity from a different circuit operated by Dominion Energy, but the lag between the outage and the restoration of power caused the IT system that controls all the facility’s operations to fail, leading to catastrophic flooding.

However, the state notice more bluntly says that the city’s failure to plan for emergencies — as opposed to the weather or unforeseeable equipment failures — was a major factor in the crisis. Those failures, VDH said, could even amount to violations of rules requiring localities to keep water treatment facilities in good working order and capable of withstanding power outages.

State officials also offered new details of why the situation may have become so bad so quickly.

According to the notice, only three waterworks operators were at the plant, but more specialized personnel such as electricians and maintenance experts were not. When the power went out, those operators “could not or did not” conduct the manual switch to the other power source and “did not or could not manually operate valves to prevent the flooding” that occurred after other systems failed.

Staff “did not adequately respond to the power outage, possibly because of a lack of awareness of what needed to happen quickly, ineffective training, or other reasons,” ODW wrote.

Furthermore, the notice states that Richmond officials did not notify the state water office “of the critical nature of operations” until 2:30 or 3 p.m. on the day of the failure — at least seven hours after the initial power outage.

The office also announced it will conduct its own investigation into the Jan. 6 failure, with an expected completion date of April 7. The state has already issued a request for proposals for architecture and engineering firms to assist VDH.

In a statement put out ahead of the notice being made public, a city spokesperson took a conciliatory tone, saying the step “is a necessary and planned part of working with VDH on a corrective action plan and one that will help ensure stable and resilient functionality at Richmond’s Water Treatment Plant.”

Federal and state concerns

The notice of alleged violation, the first step in an enforcement process overseen by the Office of Drinking Water, comes more than two years after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a scathing report on the condition of Richmond’s plant.

The health department’s move to crack down on Richmond after a major plant failure underscores questions about why regulators and city officials didn’t appear to treat the 2022 EPA report with a greater sense of urgency.

It’s not clear exactly what happened in the two years since the EPA issued its report, which flagged dozens of problems with how the plant was being operated and maintained, ranging from corroded pipes and leaking fluids to overgrown vegetation, faulty alarms triggered by the IT system and — perhaps most critically — a lack of an up-to-date emergency response plan.

The EPA never formally concluded its review of Richmond’s plant and told The Richmonder it has had an “ongoing” investigation into the matter since 2022.

Members of Richmond’s City Council and Mayor Danny Avula, who assumed office six days before the plant failure, have said they were unaware of the EPA report.

EPA spokespeople have said the federal agency officially sent its report to the city in October 2022, although a city spokesperson previously told WTVR the Department of Public Utilities wasn’t presented with its findings until August 2024. Despite the litany of concerns that document outlined, none of them were considered formal violations — a designation that triggers public notice requirements.

“The report is not a final determination of facts or liability,” said Kelly Offner, a public affairs specialist for the EPA. “Federal law provides for issuing violations for non-compliance.”

Offner said she couldn’t comment further on the case because the investigation remains open.

On the state level, VDH officials waited until Oct. 11, 2024, to request a written response from the city about what was being done to address the issues raised by the EPA two years prior. That step was taken, according to ODW Director Dwayne Roadcap, due to a perceived “lack of progress” that was fueling “deeper conversations about compliance.”

“As you are aware, the regulations establish baseline standards for operating a water system to ensure the safety and quality of drinking water for our communities and customers,” wrote Toby Bryant, an engineer for ODW’s Richmond office. “The Office of Drinking Water would greatly appreciate your prompt response detailing the current status of addressing the areas of concern and any progress achieved thus far.”

On Oct. 18, former Richmond Department of Public Utilities Director April Bingham wrote back, according to documents The Richmonder obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. She asked Bryant for at least six weeks to review the 2022 report and indicated she could provide a formal response by Dec. 6.

“As the newly appointed Director for DPU and the newly appointed Deputy Director Sr. for the Water Utility……Eric Whitehurst and I look forward to working with you and your team as we focus on safe and reliable service to the region,” replied Bingham. Former Mayor Levar Stoney appointed Bingham to lead DPU in December of 2021, nearly three years before she referred to herself as “newly appointed.”

In late November, Bingham asked the EPA for an extension of the original deadline to Dec. 20, noting the city had recently observed three federal holidays and was preparing to usher new leaders into office after the November elections.

Bingham didn’t make the Dec. 20 date either. She submitted her response on Jan. 3, three days before the plant failed.

“My apologies for the submission beyond the December 20, 2024 date,” Bingham wrote in an email sent to both VDH and EPA officials. “In addition to the recent holidays, I have been heavily involved in the transition of city administration to include a new mayor and several city council members, which contributed to the delay.”

Bingham told regulators she was available to answer questions about the city’s response.

“Without knowing how much time is needed for your review process, I have marked my calendar to check in with you by March 1, 2025,” she wrote.

As part of her response, Bingham submitted a series of photographs showing repairs and other maintenance work the city had undertaken to correct problems flagged in 2022. Those included the replacement of corroded pipes and the stopping of leaks.

But little progress appears to have been made on a crucial area of concern: the lack of an updated emergency response plan. In her response, Bingham acknowledged the EPA’s finding and said the city “has implemented steps for completion in early 2025.”

Bingham, who had a background in customer service, stepped down from her job on Jan. 15. Avula announced she would be replaced on an interim basis by Anthony “Scott” Morris, a former state water official and licensed engineer.

Bringing Richmond into compliance

Roadcap, the director of the Office of Drinking Water, said in an email that between the issuance of the 2022 EPA report and the October 2024 letter, both his office and the EPA had “informal check-ins and conversations” with Richmond water officials about their progress.

While ODW’s Enforcement Manual calls for “spoken, written and email communications” to be documented in compliance and enforcement cases, Roadcap said they were not being tracked for the Richmond plant “since ODW was not in an enforcement posture.”

“The enforcement manual and its associated compliance procedures would not apply until staff initiated an elevated posture of enforcement,” he wrote in an email. “ODW was asking for updates on the city’s response, which would not be enforcement actions that required tracking.”

On Sept. 19, 2024, his office also began its first detailed inspection of the plant since the 2022 EPA visit. Those inspections, known as sanitary surveys, are required to be done at least every three years.

Roadcap said his office “has maintained routine surveillance of city operations through monthly review of operation reports, oversight of compliance sampling results, and informal check-ins in person and via email and phone,” as well as working with the city engineer on plant construction projects.

“The responsibility to comply with applicable regulations always rests with the regulated entity who has received the inspection report with findings and areas of concern, in this case the City of Richmond,” he said. “The City must act expeditiously with appropriate planning to ensure technical, financial, and managerial oversight of the response. VDH’s role, as the regulator, is to assess whether the City of Richmond is making sufficient progress on addressing areas of concern.”

Asked why his office hadn’t taken more formal action to bring the Richmond plant into compliance after the 2022 EPA report, Roadcap emphasized in emails that the state collaborates with the EPA on compliance efforts and the level of enforcement is both “discretionary” and “contingent upon the regulant’s plan of action and its actual effort to address areas of concern.”

“Certain issues take time to resolve,” he continued. “Repairs and upgrades require funding, engineering designs, permitting, procurement of contractors, and a project plan. After US EPA and ODW believe the regulant has had sufficient time to address areas of concern, and there is a new concern that the regulant is taking too long to resolve areas of concern, then there is an escalation of compliance effort.”

Additionally, he said that because ODW only has about 100 staff, “a consideration … is to always balance our limited resources.”

Under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, the Virginia Department of Health has the primary enforcement responsibility for upholding drinking water standards in the state, with an array of tools at its disposal to ensure that waterworks are meeting the requirements.

It’s typical for state officials who encounter problems at waterworks to first work informally with their operators to bring them back in line with the law before resorting to more formal enforcement actions such as consent orders and monetary penalties.

The notice of alleged violation is generally the first step in that process, outlining what violation may have occurred and what steps the operator should take to fix it. From there, officials can move to emails or phone calls, a “letter of agreement” — a document that is unenforceable but lays out a corrective action plan and schedule — a warning letter asking for a compliance meeting with the state, a consent order and then informal and formal hearings.

In a 2021 audit, Virginia’s Office of the State Inspector General found “inconsistencies” throughout the state in how the Office of Drinking Water was ensuring waterworks complied with drinking water rules and concluded it was “not using all enforcement tools” state law allowed it.

In particular, it found the office’s decentralized approach to enforcement, which allowed regional offices to develop their own individual methods for getting waterworks into compliance, “can lead to field offices’ lack of proper documentation to support a public waterworks return to compliance or may cause delays in the appropriate escalation of enforcement action.”

The audit also found a widespread reluctance to take more forceful enforcement actions, such as assessing penalties.

Instead, the office “supports the use of technical assistance (e.g., site visits, one-on-one counseling, workshops and resource referrals) for [public water systems] rather than impose penalties as the best way to bring regulatory violators back into compliance,” the inspector general found.

“This may be affecting the timeliness of actions,” he continued. “ODW’s reluctance to use such enforcement practices could signify to waterworks, even if inadvertently, that the correction of violations is not important.”

This story has been updated with more comments from ODW Director Dwayne Roadcap.