Skill game company sues Virginia AG, Henrico prosecutor, claiming ‘ongoing harassment’ from officials who say machines are banned

The next battle in Virginia’s long war over skill games will be fought over a handful of the slots-like machines in the back of a Richmond-area Buffalo Wild Wings.

After Attorney General Jason Miyares and Henrico County Commonwealth’s Attorney Shannon Taylor both indicated the machines were in violation of the state’s gambling laws, one of the top players in Virginia’s skill game industry is fighting back by suing the two public officials.

The lawsuit, filed Friday in Henrico, aims to stop what it describes as “ongoing harassment” of skill game companies and their partners by state and local officials tasked with enforcing Virginia’s laws.

The suit is being brought by Belle Holdings Inc., the owner of the Buffalo Wild Wings off Broad Street in western Henrico, and Queen of Virginia Skill and Entertainment, the Virginia affiliate of national skill game company Pace-O-Matic. Belle Holdings operates eight Buffalo Wild Wings franchises in Virginia, according to court filings.

Virginia’s ban on skill games went into effect in late 2023, but the lawsuit argues some machines are still legal and Miyares and Taylor have overstepped their authority by saying otherwise.

“Defendants’ conduct has unfairly painted QVS as a scofflaw and a lawbreaker based on its manufacturing and distribution of a legal gaming device in Virginia,” the suit alleges.

The attorney general’s office declined to comment, citing a pending investigation.

Depending on how the suit progresses, the case unfolding in the Richmond suburbs could determine whether current Virginia law still allows skill games to exist as long as players don’t insert cash directly in the machines. If the plaintiffs lose and a court rules the ban still applies, it could give law enforcement officials a legal green light to go after the machines all over the state.

The machines at issue in the case are the same ones The Richmonder reported on in a Sept. 12 story that revealed Pace-O-Matic’s new strategy.

The case also creates the unusual dynamic of putting the Republican attorney general and one of the Democrats running for his office on the same side against an industry that had previously cultivated many political allies in both parties. If Taylor were to defeat former delegate Jay Jones and win the Democratic nomination for attorney general in 2025, she’d be running against Miyares next November.

Taylor said she had not yet been served with the lawsuit and therefore couldn’t comment on it yet.

Stephen Mutnick, a lawyer representing Belle Holdings, said the Buffalo Wild Wings owner believed the machines were legal and "in no way was it ever their intent to operate an illegal game."

"Belle believes that this issue is best resolved by a court and will let the legal process run its course," Mutnick said.

The suit takes direct aim at Miyares, accusing him of “selectively” enforcing the law against Queen of Virginia/Pace-O-Matic based on faulty legal reasoning.

“Essentially, Attorney General Miyares has wielded an unofficial legal memorandum (albeit on official OAG letterhead) to act as both prosecutor and judge against QVS and its business partners,” the suit says, referring to a September memo Miyares sent to prosecutors, sheriffs and chiefs of police around Virginia.

Most skill games closely resemble traditional slot machines, with wins dependent on whether matching symbols turn up on a randomized grid. However, they’re less passive than traditional slots, often requiring players to touch the screen in order to complete a winning pattern.

Stanley Law Group fires back at Miyares

Though the suit repeatedly questions the sitting attorney general’s authority to interpret state laws, Queen of Virginia also touts the legal authority of former attorneys general who have worked as paid lobbyists for the company in Virginia.

The suit includes a letter from former attorney general Tony Troy, the law partner of state Sen Bill Stanley, R-Franklin, at the Stanley Law Group. After Miyares told Virginia prosecutors he considers the machines illegal, Troy wrote to the Virginia Association of Commonwealth’s Attorneys to argue Miyares is wrong.

“As a former Attorneys General, I am stunningly disappointed in the quality and substance of the Attorney General’s legal analysis,” Troy wrote in an Oct. 2 letter attached to the suit and written on the official letterhead of Stanley’s law firm.

The lawsuit references a similar letter by former attorney general Jerry Kilgore, the brother of state Del. Terry Kilgore, R-Scott. Both Jerry Kilgore and Troy have previously registered with the state to act as lobbyists for Pace-O-Matic.

When the General Assembly was considering legalizing skill games earlier this year, the state’s ethics council ruled Stanley didn’t have a conflict of interest in the matter despite his law firm’s close ties to one of the biggest skill game companies operating in Virginia. The Senate appointed Stanley, one of the General Assembly’s most vocal champions of the skill game industry, as one of the few lawmakers working out the final version of the bill.

Womble Bond Dickinson, the same law firm that worked with Stanley in an earlier but ultimately unsuccessful effort to challenge Virginia’s ban on skill games, is representing Queen of Virginia in the new case.

Pace-O-Matic has become a major lobbying force in Virginia, contributing tens of thousands of dollars to state lawmakers on both sides of the aisle as the company has sought to overturn Virginia’s ban on its machines. A Pace-O-Matic spokeswoman declined to comment on the new lawsuit.

The General Assembly passed legislation to repeal the ban earlier this year, but that effort was vetoed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin. At the time, the governor said the industry-backed legislation should have had a higher tax rate and more safeguards in place to limit the spread of the machines in areas that might not want them.

After that intensive lobbying push failed, Pace-O-Matic/Queen of Virginia reworked the machines and claimed the new versions are compliant with state law despite the General Assembly’s effort to ban skill games.

The twist with the new “QVS2” machines, the company has claimed, is that they don’t require players to insert cash directly. Instead, they give money to a bartender, cashier or other middleman and that person remotely activates digital credits on one of the machines. Because state law defines a skill game as a machine that requires “insertion” of currency, tokens or a “similar object” to play, Pace-O-Matic’s attorneys contend the new system is legal because nothing is being inserted.

Miyares and Henrico law enforcement officials appear to disagree.

Company claims it’s facing ‘insolvency and dissolution’

On Oct. 15, the lawsuit states, Miyares sent the Buffalo Wild Wings owner a civil investigative demand seeking a wide variety of documents about the skill games at the business as part of an investigation into possible illegal gambling devices and potential violations of the Virginia Fraud Against Taxpayers Act.

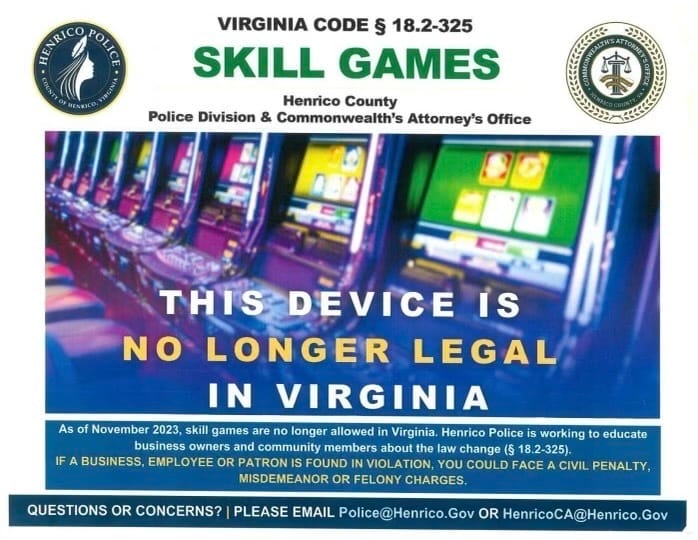

On several occasions in October and November, the suit says, Henrico police visited local businesses, including the Buffalo Wild Wings, and distributed fliers jointly crafted with Taylor’s office. Those fliers said the machines were illegal and reminded business owners that violations could bring criminal charges, fines of up to $25,000 per machine and seizure of the machines.

Henrico officials also distributed signs declaring “THIS DEVICE IS NO LONGER LEGAL IN VIRGINIA” and encouraged business owners to “place them on the gaming devices explaining why it is out of service.”

Under that “pressure,” the suit says, the Buffalo Wild Wings owner made the “difficult decision” to temporarily turn the machines off. Other businesses are making the same decision in response to “baseless legal threats” inspired by the attorney general’s conclusion the machines are illegal.

“The suspension of QVS2 game operations by Belle and others has caused irreparable, ongoing harm to QVS, including but not limited to a drastic diminution of revenue that if not allayed will result in QVS’s insolvency and dissolution,” the lawsuit says.

The suit asks the court to block the civil investigative demand from Miyares, declare the new machines compliant with state law and block Miyares and Taylor from enforcing the skill game ban against the new machines.

The letters Henrico authorities have been distributing to businesses with skill games didn’t indicate that authorities would immediately fine or punish them.

“We regret to inform you that recent legislative changes (2023) have rendered Skill Games illegal within our community,” reads a letter from both Henrico police and Taylor’s office. “We understand the impact this may have had on your operations and livelihoods, and since then, have permitted a grace period to allow our businesses in the community to adapt to this new legal framework.”

The letter said county officials would first try to educate businesses in the law and encourage them to post signs explaining why the machines are off. Any “possible felony violations” would come later, it said.

Pace-O-Matic and its representatives, who have made well over $1 million in political contributions in Virginia, have told lawmakers the company wants its machines to be taxed and regulated and wishes to comply with Virginia law. Regardless of their legal status, any machines the company is operating today aren’t subject to gambling taxes and regulations.

The lawsuit could be decided based on how the court chooses to define what words like “insertion” and “object” mean.

The attorney general has said those terms are broad enough they also cover digital credits or even the addition of lines of computer code that activate a machine once a player has given money to a cashier or bartender.

Pace-O-Matic’s attorneys contend those terms should be read more literally and that state officials can’t add words to a law that weren’t put there by the General Assembly.