School leaders want to revisit state performance agreement, saying Richmond is 'held to a different standard'

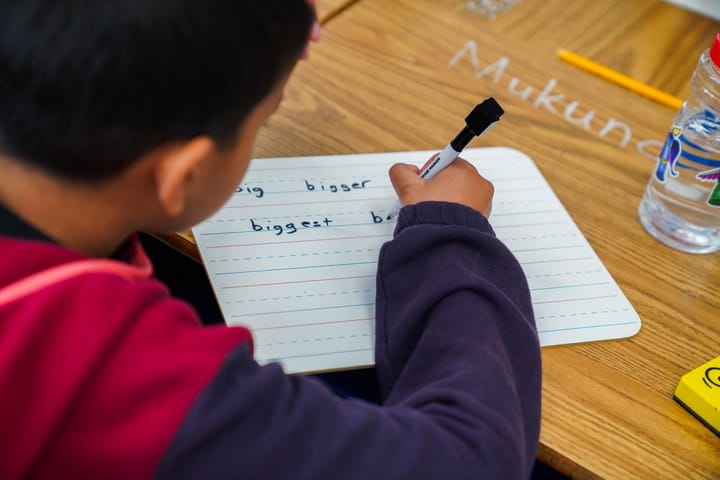

Members of the Richmond School Board and Superintendent Jason Kamras criticized an academic improvement agreement the school division entered into with the state in 2017 as setting unfairly high expectations and providing few measurable goals.

“We’ve been held to a different standard,” said Chair Dawn Page at a governance training the nine-member board attended in Charlottesville on Sept. 20.

Telling the board the only way for Richmond to exit the agreement “is to be at 100% accreditation,” Kamras said, “I’ll put it to you this way: Neither Henrico nor Chesterfield have 100% of their schools fully accredited.”

Asked about the board’s criticisms, Todd Reid, senior communications adviser for the Virginia Department of Education, noted that accreditation results released yesterday show Richmond currently has 20 schools rated as accredited with conditions — “the most of any division in the state,” he wrote in an email.

“Realizing that having 100% of schools be ‘Accredited’ is a high bar, which of their 20 schools currently ‘Accredited with Conditions’ is the Richmond City School Board suggesting allowing to continue to underperform?” he continued.

The agreement with the state, known as a memorandum of understanding (MOU), requires the city school system to follow a corrective action plan to ensure it meets the state’s Standards of Quality, the educational requirements set by the Virginia Board of Education.

Richmond has been operating under the MOU since 2017, after former Richmond Superintendent Dana Bedden asked the state Office of School Improvement to conduct a comprehensive review of how the division was doing. At the time, only 17 of the system’s 44 schools were accredited, and the state review identified serious deficiencies in nearly every aspect of how the school system was functioning.

The MOU not only required that Richmond schools develop a corrective action plan but mandates regular meetings between school system leaders and the state, state oversight of spending and instructional programs, and School Board and superintendent participation in annual training conducted by the Virginia School Boards Association.

In April, State Superintendent Lisa Coons notified the School Board it was violating the MOU because it had failed to satisfy its annual training requirement. The board also struggled to schedule its 2024 training but ultimately met at the VSBA offices in Charlottesville on Sept. 20.

“We’re finally here at the table together,” said Cheryl Burke, the 7th District representative, during the meeting. “And we’re here at the table together because it is required in the MOU to do so.”

Violating the MOU can come with consequences. If the state superintendent determines the School Board “has failed or refused” to meet any of its obligations, the MOU dictates that the state shall withhold some or all of the division’s at-risk add-on funding, the additional money Virginia gives school systems that have large numbers of low-income students.

The agreement also specifies that it will remain in force “until all schools are Fully Accredited.” If full accreditation isn’t achieved by the beginning of the 2025-26 school year, the Office of School Quality will be allowed to put a non-voting representative on the School Board.

That high bar has rankled some members of the board.

“That is always going to be our Achilles heel until we as a governance team demand some equity,” said 6th District member Shonda Harris-Muhammed, who has criticized the MOU in the past, at the Sept. 20 meeting.

Reid, however, denied that the bar has been set higher for Richmond than other divisions.

“Having reviewed the current MOUs for the five school divisions with MOUs currently in place, all five are held to the standard of having all their school[s] reach ‘Accredited,’” he wrote in his email. “Unlike Richmond City Public Schools, which is only required to meet that standard for one year, both Prince Edward and Danville City are required in their MOU to meet that standard for two consecutive years.”

Richmond Public Schools currently has 24 schools that are fully accredited, five of which achieved accreditation this year. They include Thomas Jefferson High School, Dogwood Middle School and Bellevue, Overby-Sheppard and Reid elementary schools.

Fifth District member Stephanie Rizzi pointed out that Richmond Public Schools has a disproportionate number of low-income students compared to surrounding jurisdictions, saying “that also needs to be taken into consideration when they are giving us these requirements.”

The full accreditation requirement wasn’t the only issue raised with the MOU. Kamras told Virginia School Boards Association governance trainers that the document “is so expansive that it sort of boils down to ‘be a better school division.’ And so it’s not particularly helpful in terms of specific goals.”

“This is a critique of the MOU that we have shared, and to the state’s credit, they have acknowledged it, and I think they’re going to rethink how it actually really works,” he said.

Kerri Wilson, a consultant for the VSBA who helped lead the Sept. 20 training, agreed with Kamras that “there are very few measurable objectives that are specific within this MOU.”

Confusion also surrounded the number of meetings that the state and school division have held on the MOU. The agreement requires that the state superintendent of public instruction and state Board of Education president meet with the Richmond School Board chair “at least twice per year.” It also requires meetings every two months between the Office of School Quality and the Richmond superintendent “and appropriate staff” to discuss progress on the corrective action plan and review data.

During the governance training in Charlottesville, Kamras told board members he and former chair Rizzi had participated in an annual meeting, but that monthly check-ins with the state had not been occurring.

The Virginia Department of Education said there have been 40 meetings this year between department staff and Richmond Public Schools leadership, in addition to “ongoing discussions” with Kamras.

Alyssa Schwenk, a spokesperson for the division, said the discrepancy is “just a matter of differing definitions.”

“Board and superintendent were speaking specifically about the corrective action plan meetings, which happened on a regular (usually quarterly) basis, but the last one was in May, 2023,” she wrote in an email. However, she noted that VDOE and Richmond Public schools staff meet every two weeks to discuss various issues, including school improvement efforts.

Virginia is in the process of rolling out a new way of rating schools that provides both an accreditation score evaluating how the school is meeting state requirements and an accountability ranking focused on student mastery of material, growth and readiness. The overhaul has been backed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin, who has been outspoken about his belief that Virginia’s educational standards have declined.

The new system is expected to go into effect for the 2025-26 school year. Projections from the Virginia Department of Education show that if schools were evaluated based on data from the 2022-23 school year, roughly 60% of divisions would be classified as “off track” or in need of intensive support. About 40% would be considered “on track” or “distinguished.”

Kamras said that he believes the state is “receptive” to conversations about the MOU but needs to navigate the rollout of the new system first.

“I think that creates an opportunity to kind of reset,” he said.