In unpredictable contest, Richmond mayoral candidates pitch City Hall reset

As a group of her friends and supporters sipped mimosas at a downtown steakhouse over Labor Day weekend, Richmond mayoral candidate Michelle Mosby was feeling good about her chances.

Black voters showed up for former President Barack Obama, Mosby told a group of women gathered for her Pretty in Pink brunch, and they’ll show up again this year with Vice President Kamala Harris at the top of the Democratic ticket.

“I believe it is ours to win,” said Mosby, a 55-year-old hair salon owner, nonprofit founder and former Richmond City Council president hoping to be the first Black woman elected mayor of Virginia’s capital city. “People on the other side, even with our little bit of money, are scared y’all. ‘Cause it’s ours to win.”

Not everyone shares her certainty.

The 2024 mayoral race reflects the changing look of a city seeing its demographics shift as more newcomers move in. The city’s population trends, as well as the lack of clear political heavyweights in a field of five candidates, have made for an unpredictable contest with two months to go.

Mosby, who left the City Council in 2016 to make an unsuccessful run for mayor that year, is competing against longtime public health official Dr. Danny Avula, City Councilor Andreas Addison, former finance professional Harrison Roday and self-described community organizer and entrepreneur Maurice Neblett.

A lack of big names and big policy differences has, so far, made for a fairly tame campaign, with most candidates hitting broad themes about rebooting City Hall and making local government work better for everyone.

“This is a different election than anything we’ve seen,” said longtime political analyst Bob Holsworth. “Because we don’t have candidates who come with a boatload of experience and with a ready-made constituency.”

A poll of the race conducted for Mosby’s campaign in early July showed her and Avula as the strongest candidates, with Mosby running slightly ahead. In that survey, 22% of respondents said they were supporting or leaning toward Mosby, compared to 16% for Avula, 5% for Addison, 4% for Neblett and 2% for Roday.

“The people have spoken early,” Mosby said in an interview when asked whether she sees herself as the frontrunner. “And I think they’re going to show Nov. 5 that they want someone that IS Richmond. That has experience in local government.”

In a recent interview, Avula — who’s making his first run for elected office after leading Virginia’s vaccination effort during the COVID-19 pandemic — said he agreed Mosby could get a boost from voters turning out to support Harris.

“I make sure I don’t let people forget that she’s also Indian,” he said with a laugh, referring to the South Asian identity he shares with Harris, whose mother was from India.

The Mosby campaign’s poll, which The Richmonder obtained, showed about half of the 500 likely voters who responded were undecided, a sign there’s room for movement as peak election season arrives.

Avula said the poll showing Mosby as an early favorite was consistent with his campaign’s view of the race. But he noted he’s well ahead of Mosby in raising money to communicate a “future-looking” message as more voters tune in.

Avula said his campaign is based on a “heart for justice” and a record of successful government management shown, he says, by the 2021 vaccination effort he helped turn around after a slow start .

“It just really heartened me about the effectiveness that government can have when it is focusing on the right things,” Avula said. “When it is really outcomes-focused. When it's partnering with the private sector. When it is listening deeply and partnering with the communities that we serve.”

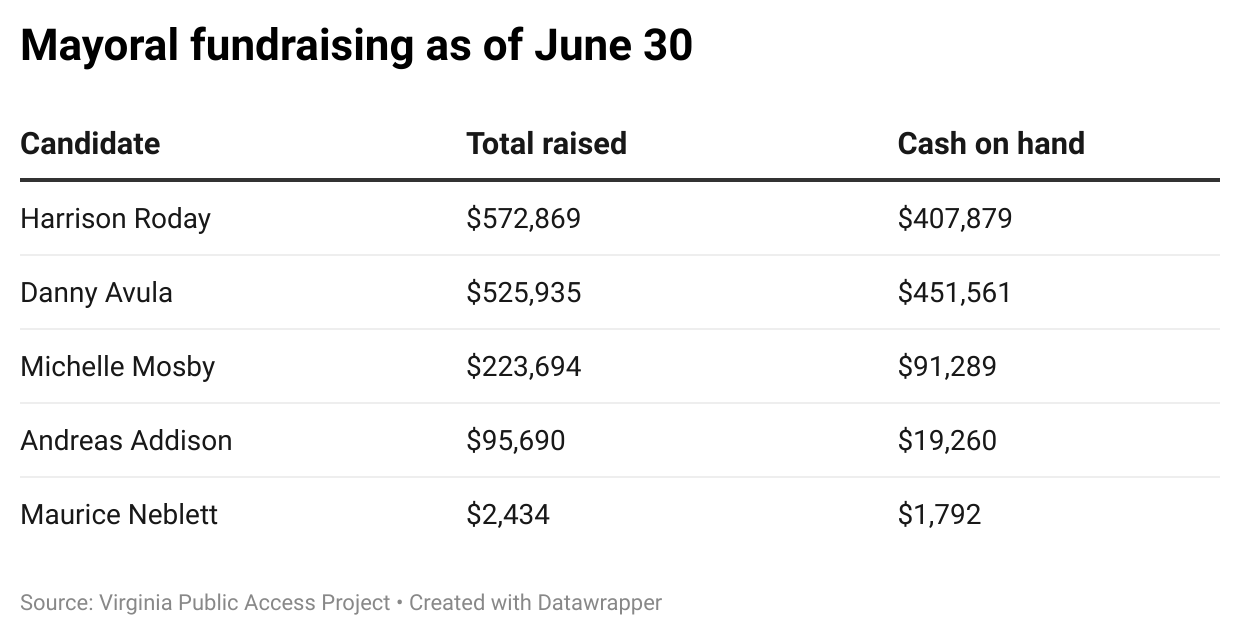

The biggest wild card among the mayoral contenders might be Roday, a 33-year-old Henrico County native making his first political run after working for a manufacturing-focused private equity firm in New York. Helped partly by his business and finance connections, Roday had raised more money than all his competitors as of the end of June.

Despite having an upper class bio that’s not exactly tailor-made for Richmond politics, Roday has received attention-grabbing endorsements from the progressive activist organization New Virginia Majority and the Richmond Crusade for Voters, a group that focuses on Black voter engagement.

With those endorsements and the money to run a substantial media campaign, Roday expressed confidence that many undecided voters will look his way despite his inexperience.

“I am fortunate to have a lot of opportunities in my life,” Roday said in an interview. “I think it’s very obvious that opportunities are not distributed in our society in the way that they should be. And government’s purpose should really be to, among other things, address that issue.”

Roday is also the founder of a nonprofit that provides access to capital for “historically marginalized small businesses and places.”

Addison, 42, a gym owner, is running as an experienced city official who already knows the ins and outs of City Hall. He’s also emphasizing concrete policy results over his two terms such as helping ensure local bus service remained fare-free after the pandemic.

“I believe we’ve got novices and a bureaucrat that are running for this office that believe that this is a way to advance their personal pursuits or goals,” Addison said in an interview. “We’ve never had a mayor come from council that actually understands the job.”

Addison was well behind Avula and Roday in fundraising reports filed over the summer. The Mosby campaign’s poll found Addison trailing Mosby and Avula but slightly ahead of Roday.

Rounding out the field is Neblett, who is widely seen as a longshot candidate. Neblett has been an energetic presence at numerous mayoral forums with his better-known and better-funded opponents, but he has reported minimal fundraising and has said he’s mostly running his campaign on his own.

“I’m a common man going to politics,” he said at a recent forum when pressed on whether he feels qualified to be mayor.

‘Nobody has made up their mind’

Though the mayoral race is technically nonpartisan, the candidates are running as Democrats.

The Richmond City Democratic Committee endorsed Stoney in the crowded 2016 race for mayor, but the local party isn’t planning to make any endorsements this year, according to RCDC Chairman Jerome Legions. Legions said in an email that the party felt that making an official selection for mayor “would cause friction in the committee.”

So far, there have been few major disagreements on policy or political philosophy. All the candidates have stressed the need to make City Hall do a better job of handling basics like tax and utility bills, make housing more affordable, improve the city’s underperforming public schools and adopt new strategies for reducing gun violence.

They’ve all promised to usher in an administration that’s more transparent, accountable and responsive to the needs of Richmond residents.

The remarkably similar rhetoric being offered to voters, Holsworth said, is probably a factor in “why nobody has made up their mind.”

“Politics is about contrasts and visibility. You’re out in front on something where everybody else is trying to catch up to you or they’re different than you,” Holsworth said. “At least up to now… nobody has done it.”

Stoney — the target of implicit criticism from candidates who say City Hall still suffers from dysfunction and a lack of accountability as his eight-year administration winds to a close — has also publicly faulted the mayoral contenders. At a news conference last month, Stoney said no candidate is breaking through because no one is laying out a big-picture narrative that’s resonating.

“Part of this job is about vision-casting. Give me an idea of what type of city we are going to be in a decade,” Stoney said. “Because there’s a good chance that you may hold this office for eight years. And right now, residents are telling me: ‘Mayor, I don’t have a clue who should succeed you.’ And I join them. I don’t have a clue either.”

Stoney, who’s now running for lieutenant governor, has said he intends to endorse a mayoral candidate but hasn’t made up his mind. With his would-be successors emphasizing change as a dominant theme, it’s unclear who would welcome Stoney’s support.

Demographic change

The election taking shape could also reflect the city’s longstanding racial and class divides, and the reality (as seen in the recent pair of failed casino votes) that Richmonders’ voting preferences can still diverge sharply from neighborhood to neighborhood.

The community-level battle for votes matters immensely under the strong mayoral system Richmond enacted two decades ago. To win the mayor’s office on Election Day, the victor has to carry at least five of the city’s nine political districts. That effectively creates a miniature version of the Electoral College, preventing candidates from running up the score in some areas and ignoring others.

Black candidates have won every election so far under the strong mayor system, which incorporated the five-of-nine districts rule largely to preserve the voting strength of Black communities. However, the city’s Black voting age population fell from 51.5% in 2000 to 38% in 2020, according to U.S. Census data compiled by city officials. During that same period, the white voting age population increased from 43.1% to 45.5%.

The Latino voting age population, meanwhile, jumped from 2.5% to 9%, bringing a new dimension to a city long accustomed to thinking in terms of Black and white.

Even with those changes, significant support from Black voters is still seen as critical for any would-be mayor.

Mosby, who represented South Richmond’s majority-Black 9th District when she served on the council and leads a city-funded nonprofit focused on prisoner reentry services, has at times argued she’ll bring a unique level of credibility on tough issues like gun violence and youth behavior.

“We need those that are going to go in and talk to our parents and say ‘Hey you guys, the teacher can’t be you. You’ve got to parent from the house,’” Mosby said at the brunch event. “But you’ve got to have someone that’s strong enough to say that. I can do it because I come from these communities.”

Mosby has a long list of endorsements from Black political and faith leaders, including former Mayor Dwight Jones, state Dels. Delores McQuinn and Michael Jones, City Council members Ellen Robertson and Cynthia Newbille and former City Hall chief administrative officer Selena Cuffee-Glenn.

The campaign’s racial dynamics produced a tense moment at a mayoral forum last week. When candidates were given a chance to ask any opponent a question, Avula said he had heard Mosby’s team was telling public housing residents that “I don’t hire Black staff and I’ve never done anything for the Black community.”

“I know you wouldn’t say that, but what will you do to address that with your staff?,” Avula, who regularly highlights his efforts to tackle racial health disparities as the former director for the Richmond and Henrico health departments, asked Mosby.

“I first would need to ask my staff,” Mosby said. “Because, I love you, but you don’t come up. You don’t come up at the office. So it’s kind of hard for me to believe.”

If mayoral voting patterns sharply diverge by district — with Harris-energized Black voters mostly preferring Mosby and the city’s whiter precincts split between Avula, Roday and Addison — it’s possible no one will be able to build enough citywide appeal to win five districts. Should that occur, the city would see its first mayoral runoff election, with the top two finishers competing again in a head-to-head matchup in December.

When the strong mayor system was implemented in 2004, the city had six majority-Black Council districts. Today, there are four majority-Black districts, according to city data.

That decrease prompted a city commission to raise questions about whether the district-based method for electing mayors is still serving its intended purpose. If the downward trend were to continue or accelerate, the commission said in a report released last year, the five-of-nine rule could “harm rather than help Black voting strength” by giving the shrinking number of majority-Black districts less influence in picking mayoral winners.

The commission floated ranked-choice voting as a potential alternative, but recommended no changes to the mayoral system for the 2024 contest.

Contrasts begin to emerge

The candidate forums so far have been heavy on agreement, and relatively light on candidates looking to draw sharp contrasts or criticize opponents. But that appears to be changing.

On several occasions, Roday has raised doubts about whether Avula is the devoted Democrat he says he is.

It was former Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam who tapped Avula to help coordinate COVID-19 vaccination. But in 2022, Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin appointed Avula to serve as commissioner of the Virginia Department of Social Services. That’s fueled questions for Avula about where he stands on progressive priorities like abortion rights and LGBTQ equality.

“I think there are differences in whether or not you’ve been a strong, passionate advocate for Democrats and worked for Democrats to get Democrats elected,” Roday said when The Richmonder asked what contrasts he sees among the candidates. “If you are someone like me who has championed that for a long time, as has Councilwoman Mosby, or if you are someone who’s come to that lately because it’s politically convenient.”

Avula said his record will show he’s a supporter of reproductive and LGBTQ rights. Being appointed to state roles by Democratic and Republican governors, he said, shows he has a bipartisan reputation for effectiveness.

“I’m really proud of the fact that I got to lead an agency that’s sole purpose is to support low-income families,” Avula said of his time leading the Social Services Department. “It seems silly that people would try to play politics with that. I would hope that anybody who actually cared about serving people would want to take that opportunity.”

The support Mosby has received from past city leaders has contributed to the perception among her skeptics that she’s more of a throwback candidate than a change agent bringing fresh ideas about rebooting city government.

Addison pointed out she was first elected 12 years ago, and left office as his time on the City Council was just beginning. She had a great career on the council, he said, but Richmond is now “a very different city.”

Mosby has taken few shots at her opponents apart from contrasting her experience in city politics with the inexperience of the candidates she seems to see as her strongest opponents.

At the brunch, she seemed to acknowledge her biggest challenge is raising money. No matter how good a campaign’s fundraising experts are, she explained to her guests, every candidate is expected to lean on their own network of contacts. Her opponents have wealthy people in their phones, she said, “because wealthy people know wealthy people.”

In her phone, Mosby added, is “community, people, friends, neighbors.”

“Which makes my road just a little bit harder,” she said.

Election Day is Nov. 5. Early voting begins Sept. 20.