I bought an island on the James River. Then I learned its history...

My island enters the historical record on New Year’s Eve 1853, with an inauspicious tale.

The week before, a group of friends set off down the James River from Sharp’s Island on a “gunning excursion.” They returned, according to a short piece in the Richmond Daily Dispatch, on the evening of Dec. 29 “with a quantity of game.” Friday broke “extremely inclement,” and the young men holed up in a cabin on the island where “some of them engaged in firing Christmastime salutes with an old musket, while others were preparing for the feast.”

It’s impossible to know what 17-year-old George Sharp Jr. was thinking that night around 10 p.m. when he picked up a musket “that had been heavily charged and placed near the door.” When he was 15, the article tells us, Sharp was wounded in the left hand from the accidental discharge of a rifle. He recovered fully from that blast, but on this night, he wouldn’t be so lucky.

Sharp grabbed the musket in the cabin on the island bearing his family name and “without a moment’s reflection, pulled the trigger.” The musket exploded, shredding that same left hand and severing the thumb.

Imagine the scene: a group of young men, momentarily deaf from the blast, staring at their friend bleeding from his mutilated hand, on an island in the middle of the James River?

Upon arriving at his father’s house in Shockoe Bottom, a doctor examined what was left of the hand and amputated it above the wrist. Then this from the unnamed author: “When we saw the unfortunate lad, about 5 o’clock yesterday [Friday] afternoon, he was quite easy and apparently doing well.”

Seems unlikely. Welcome to the 1850s – the newspapering and anesthetic leave you wanting more.

Purchasing an island

Of course, I knew nothing of George Sharp Jr. or the island’s history as I sat in the upper deck of Philadelphia’s Lincoln Financial Field in September 2018. With my phone at 1% battery life, I was trying to put that acre of rock and sand under contract. The crowd stood and roared for the defending Super Bowl champions. I sat, pecking feverishly at the e-docs. If the phone died, it would be hours before I could charge it again. Hours during which my dream could be snatched away by some other offbeat weirdo with an island jones. But the signatures went through, I high fived my confused stadium neighbors, and two months later my family, along with nine others, closed on our very own island.

The granite of the Piedmont meets the more-easily-eroded Coastal Plain there. Literally. The final rapids in the entire James River bisect the island. The upstream half is a rocky outcrop. The downstream half has sand beaches and a surprisingly large tidal range. It’s about 75 yards from the south bank of the James to the island, and, at a manageable river level, it’s a pleasant paddle.

The island was a tangle of weeds and vines obscuring a few hardy persimmon and hackberry trees, a couple of sapling sycamores and river birches. Poison ivy was everywhere. Two friends joined me for that maiden voyage, and we picked our way along the north bank. At the highest point, where granite and the James River have done battle for millennia, we stopped and stared. There in front of us were the unmistakable remains of a house. The low walls of a brick foundation had been anchored to the rock with massive steel bars. Loose bricks lay all around. It was a revelation: This place wasn’t just a patch of rock and sand and green in downtown Richmond, much as that excited me for its outdoorsy possibilities. It had a history – a human history. How could this be? Who did this and when?

The previous inhabitants

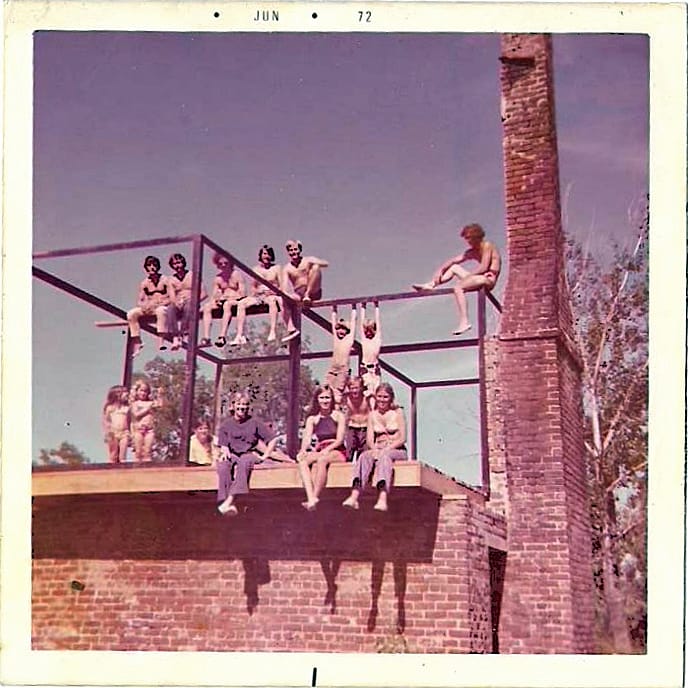

It’s been almost six years since that day. Our initial discovery led to Google searches and hours spent buried in newspaper archives. Sharp’s Island. Those two words were all I had to go on. From there I worked backwards to Henry Tenser, the local architect who bought the island in 1968 and whose dreams of an avant-garde cube dwelling were carried downstream by Hurricane Agnes.

Before Tenser was Russell Sharp, who the Richmond Times-Dispatch Magazine featured in 1950 sitting on the porch of his two-story island house watching the traffic go by on the Mayo Bridge. This was the house, I realized, whose foundation we discovered. Sharp, 69 and a widower, had a home in Woodland Heights and came and went from his island. His friend Fred Hastings, 49, on the other hand, is described as the island’s live-on caretaker.

“When Sharp comes down to the river any evening after work, he stands on the point of land under the last arch of the [Mayo Bridge]… and hulloes across the water,” the T-D’s Marvin Caplan wrote. “‘I’m always watching that point like it was the front door,’ Hastings says. He rows over from the island and picks up Sharp. Or friends. Or even a stranger if he looks sociable. ‘We’ve had some good times here,’ both men agree.”

More searches led to more tantalizing fragments. The 1922 re-enactment of John Smith and Christopher Newport planting their wooden cross at the Falls of the James, using Sharp’s Island as the famous site while thousands watched from the Mayo Bridge. The 4th of July parties held there in the late 1800s. And then, of course, poor George Sharp Jr. – Was he Russell’s father? Grandfather? – on that stormy December night in 1853.

My turn

I write this now from the cabin I just completed on Sharp’s Island. It’s the third structure I’ve built out here in six years. The first floated away in a 2020 flood. A summer thunderstorm damaged the second beyond repair. The archives are telling and not just a little haunting. Tenser and Russell Sharp’s structures I know about. But this piece hits me hardest. Richmond Daily Dispatch, March 29th, 1871: “The R.E. Lee Club is building on Sharp’s Island what is to be a beautiful little home. It is to take the place of the one that was washed away in the July flood.”

Was this “beautiful little home” to replace George Sharp Jr’s cursed hunting cabin? The timing works. If so, it was soon washed away as well. Russell Sharp’s home was built in 1895. There are many gaps in the archival record for my island getaway, but one thing is clear: Every human effort to establish a foothold on that rock has ended the same way.

People ask me why I tempt fate building this cabin. Why did the others? Won’t it come to naught soon enough? I have no ready response. I jokingly call the cabin The Ark because it will one day be a boat.

But while posterity makes clear the James River’s intentions for my island, it also offers abiding reasons to hang on, to re-build, to keep pushing that rock up the hill. In 1950 Caplan closed his piece on Russell Sharp’s sliver of urban wonder with words which ring true today:

“On a summer evening you can sit out on the porch and watch the color go out of the roses by the water’s edge…and the lights come on along the Fourteenth Street Bridge. You sit watching the lights melt together in the tumbling water; watching and hearing Richmond whiz and chug and bang around you, while you rest in a rocker remote from the city’s rush.”