Henrico weighs choice between breaking off from Richmond water system or pursuing more regional cooperation

Henrico officials are weighing whether they should invest hundreds of millions of dollars to break free from Richmond’s water system or pursue a more regional solution like an authority that would give them greater control over the utility.

The decision, which County Manager John Vithoulkas said he was meeting with Richmond Mayor Danny Avula to begin discussing Tuesday, could have major implications for city residents and the bills they may have to pay to keep the system running in the future.

In a Board of Supervisors work session Tuesday, Vithoulkas even floated the idea of Henrico purchasing Richmond’s water plant outright, although he acknowledged that “would be a very complicated transaction.”

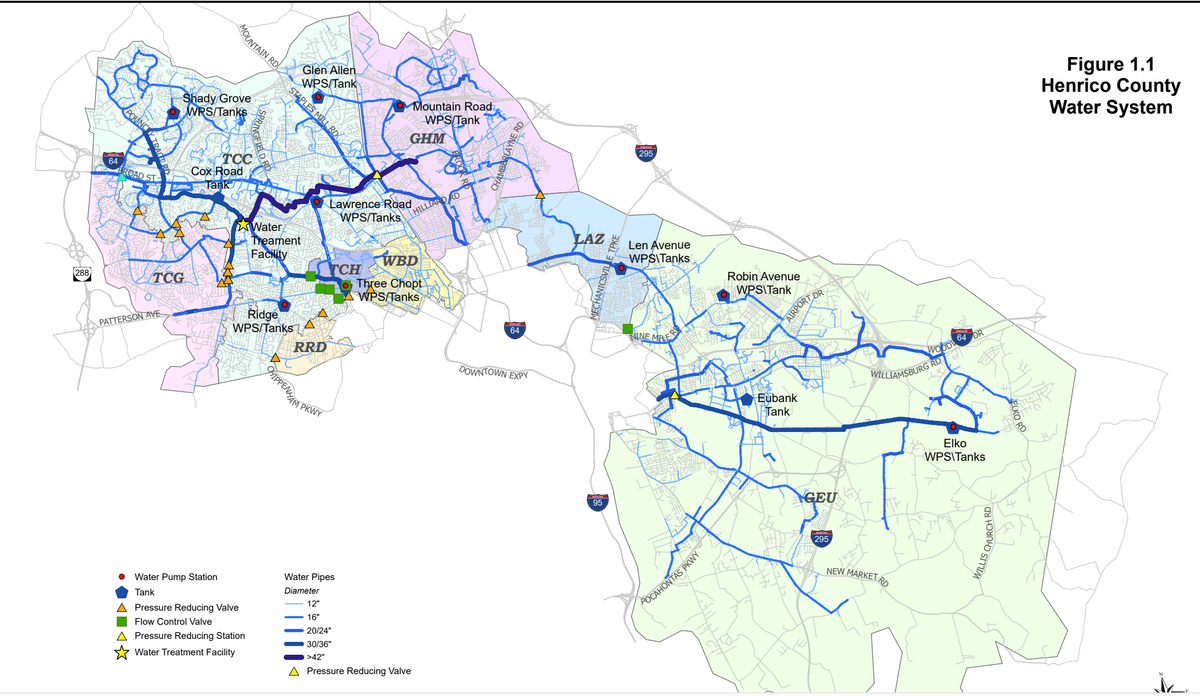

Henrico gets roughly one-third of its water from Richmond through an agreement that was signed by the two localities in 1994 and isn’t set to expire until 2040. The county is Richmond’s biggest customer, required to purchase the equivalent of roughly 12 million gallons per day of water annually.

But the failure of the city’s water treatment plant on Jan. 6 following a power outage, an event that ultimately left hundreds of thousands of customers in the region without drinkable water for nearly a week, has caused Henrico leaders to rethink whether they want to continue to be tethered to the city for a significant portion of their water needs.

“We need to do what’s best for Henrico County right now,” said Supervisor Tyrone Nelson (Varina).

Avula said Tuesday night that if Henrico pulled out of the city’s water system, the city would see a financial hit but said the more far-reaching question was, “If each locality starts to invest its own money in infrastructure, can we right-size the operation in Richmond to just meet Richmond’s water needs?”

“All of us, I think, are in agreement that having the conversation and trying to figure out whether we can make regional investments together and ultimately end up with a more sustainable system is where we’d like to be,” he said.

The mayor emphasized that the city is considering all options, although he said his administration hadn’t yet opened discussions with City Council about what comes next. An investigation by the city into what went wrong at the plant this January is also still underway.

“Do we outsource it? Do we sell it outright? Do we come up with a regional model? Do we continue to invest on our own?” asked Avula. “I think definitely we are so early on in the process that I haven’t ruled anything out.”

Several Henrico supervisors on Tuesday seemed somewhat favorable toward the idea of an authority. Nelson said he was “all in” on the idea and would likely back it in a vote, but also made it clear that if Richmond doesn’t support greater county input, he would be willing to push for more dire measures.

“If there is no water authority that we are a part of, if we're not a part of the distribution of water that comes out of the city of Richmond, you know, I know our lawyers probably don't want me to say this, but we have to break the agreement and take care of our own folk,” he said.

For Henrico, the greatest concerns center on the county’s east end, which immediately adjoins Richmond and is totally dependent on the city’s supply for its water. While Henrico has nearly finished developing the massive Cobbs Creek Reservoir in Cumberland County and began operating its own water treatment plant in 2004, the county’s existing transmission lines aren’t designed to pump enough water to supply customers in its eastern part.

“The water itself is not the concern,” said Board of Supervisors Chair Dan Schmitt (Brookland). “It’s the ability for us to transmit and distribute that water.”

Consultants Whitman, Requardt & Associates — an engineering firm that has also overseen upgrades and expansions at the Richmond plant for decades — on Tuesday laid out six options they had analyzed for how Henrico could solve that problem in the coming years.

Not all were viable. Aquifer constraints make it unlikely the county will be able to get state permission to increase its supply by digging more wells, WRA found. And while Henrico could consider building a new regional water treatment plant at a cost of almost $1.3 billion, the consultants said it was unclear whether available rivers would have enough capacity to supply it.

Other plans to build out more transmission lines to pipe water from the western to eastern parts of the county came with price tags ranging from $20 million for an immediate but limited solution to a $583 million buildout that would meet current and long-term projected demand.

Vithoulkas said a medium-term plan to construct a roughly 13-mile transmission main at a cost of $328 million could be funded through regular 5% increases to residents’ water bills that were already planned prior to last month’s water crisis.

While those investments would likely provoke some pushback — Nelson said he thought Varina residents would be split on the idea — supervisors also fretted about the costs of staying connected to a system over which they have no control and which residents and businesses now see as unreliable.

“If the city is unable to offer the reliability to our residents and the region, I would have no problem with Henrico becoming the robust supplier of water,” said Schmitt. “We have the water supply and we made the investment with Cobbs Creek.”

Still, he continued, “I would also have no problem with a strong regional partnership that offers the reliability and the redundancy.”

Regional water authorities exist throughout Virginia. By bringing together multiple local governments to coordinate their plans for meeting water demand, the authorities are supposed to keep down infrastructure costs while also keeping neighboring localities from getting into fights over water usage. In the Richmond area, they include the Appomattox River Water Authority, which serves Chesterfield, Dinwiddie and Prince George counties as well as the cities of Petersburg and Colonial Heights.

But in Richmond, surrounding counties remain customers of the city’s water system rather than partners in its operation. While a proposal to create an authority was floated in the 1990s, it was scuppered after concerns from the counties over costs.

Whether the situation is different this time around remains to be seen. Unlike in the ’90s, Virginia now requires local governments to develop water supply plans together instead of on their own, and Vithoulkas has said the county should see where discussions go. But Schmitt also emphasized that he would need Richmond to demonstrate “urgency and speed” as well as being clear about the financials and the redundancies any plans would offer in order to back any partnership.

Henrico also, he said, will need some control.

“If this county is going to invest dollars to get that plant up to a standard level to provide stable water to Richmond residents and Henrico County residents and beyond, Hanover residents, well then this county is going to have a stake in how it's managed,” he said.

Reporter Graham Moomaw contributed to this story.

Contact reporter Sarah Vogelsong at svogelsong@richmonder.org or reporter Graham Moomaw at gmoomaw@richmonder.org.