Discovery of 742 potential graves raises new questions about how to handle Confederate marker in Manchester

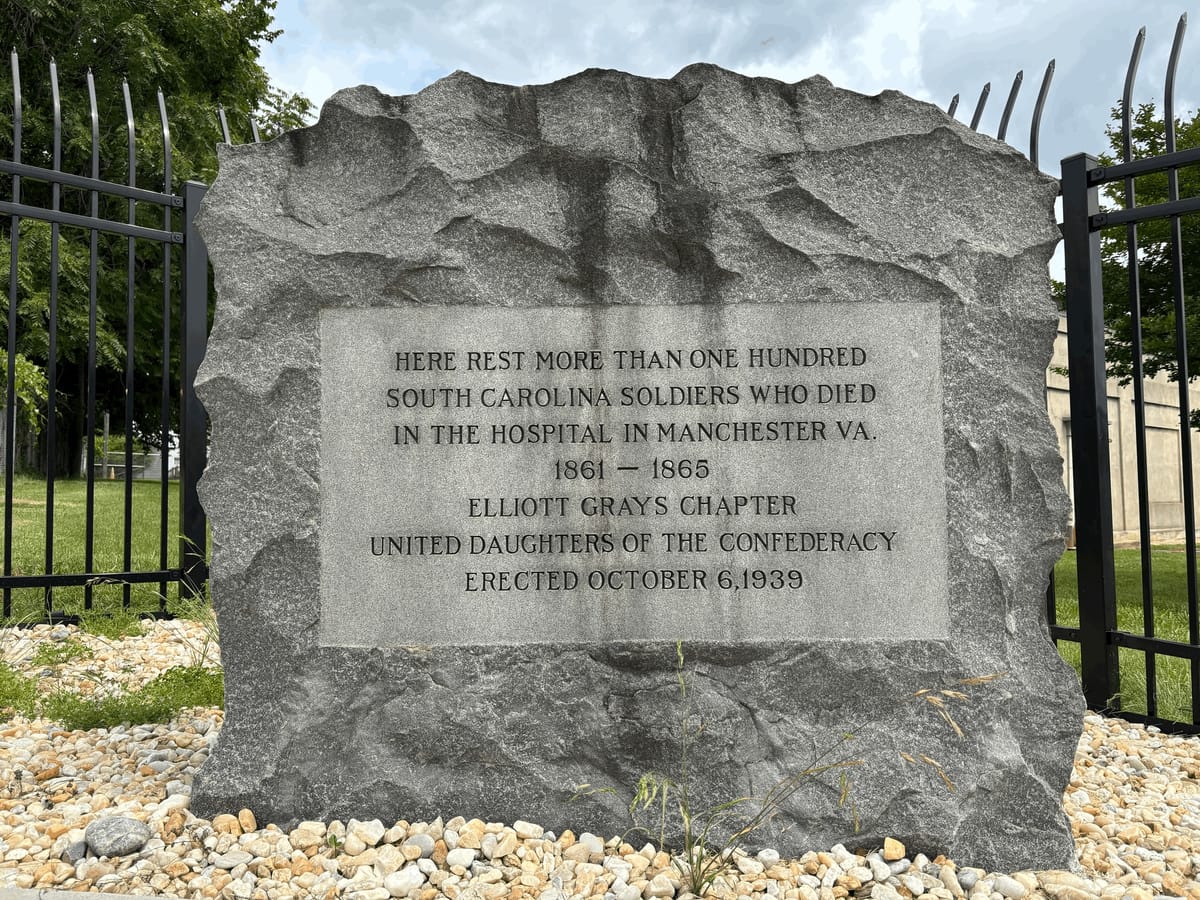

When Richmond officials put up a bench near a roadside memorial in Manchester that says more than 100 Confederate soldiers from South Carolina were buried in the area, it drew pushback from critics who saw it as a sign the former capital of the Confederacy was still spotlighting the Lost Cause.

The bench — installed in 2023 at the request of a Virginia man who wanted better access to a city-owned site where he says one of his ancestors is buried — was later removed. Some wanted the memorial to go too, partly because it wasn’t clear if it accurately described what lay beneath the ground.

Officials now have evidence there are bodies there. Apparently a lot more bodies than anyone thought.

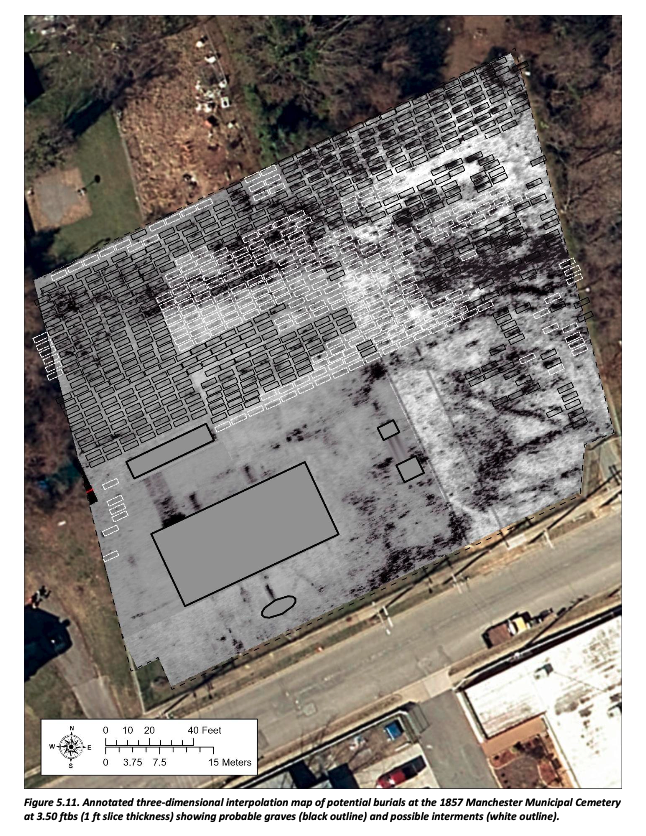

Through the use of ground-penetrating radar and thermal images taken by drones, a company hired by the city found what appear to be at least 742 unmarked graves across nearly 1.3 acres.

On the surface, there’s little to suggest the property at 2313 Wise Street was used as a graveyard starting in 1857 and continuing into the Civil War era. The city built a natural gas booster substation on the land in 1931. That Department of Public Utilities facility still stands in a fenced-in, grassy area on an otherwise normal-looking city block.

After analyzing images of buried objects, archaeological surveying firm TerraSearch Geophysical identified 472 “probable” graves and 270 “possible” graves at the site. There could be more, the researchers noted in an 86-page report, because the evidence suggests the burial ground extends into adjacent lots. The research also indicated there could be additional graves under the road.

“The data collected at the 1857 Manchester Municipal Cemetery has identified intact and sensitive resources, and any future ground disturbance should be avoided if possible,” the TerraSearch team concluded. “If ground disturbance is unavoidable, it is recommended that a qualified archaeologist monitor those activities within the bounds of the lot and beneath Wise Street.”

Some bodies were dug up when the gas facility was being built, according to newspaper accounts from the time, which may have inspired the United Daughters of the Confederacy to put up the marker in 1939. City officials passed a resolution approving the marker that year. That resolution said the marker would be put up on city property at the UDC’s expense, but would be “perpetually cared for and maintained by the City of Richmond.”

The lack of grave markers makes it difficult to determine who exactly is buried at the site, but the report says it likely contains “remains of private citizens as well as deceased soldiers from military hospitals located in the area.”

The city commissioned the survey to get clarity on what’s under the property it owns, because there was some indication bodies had been moved elsewhere at some point after the war. The research found there was no coordinated action to move all the bodies to Richmond’s more intact historic cemeteries.

“While there is no definitive record of wartime burials or the post-war removals, this research makes a circumstantial case that the property was used for wartime burials and that there have been no substantial postwar reinternments at Maury, Hollywood, or Oakwood cemeteries,” the report says. “The research also indicates that soldiers from states other than South Carolina may have also been buried here.”

What the city intends to do with the information it received is not yet clear.

“In consultation with historians and appropriate officials at the state and local levels, the city is developing an access plan to the site which would allow visitation to descendants of those believed to have been interred there and to others interested in genealogical research,” city officials said in a news release Friday. “Once finalized, that plan will be announced and available on the city’s website.”

Former Mayor Levar Stoney has touted the removal of most of Richmond’s Confederate iconography as one of his marquee achievements during his eight years in office, one he is spotlighting in campaign ads as he now seeks the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor.

As the Stoney administration faced questions over why it was treating the marker in Manchester differently from other Confederate symbols, according to the Richmond Free Press, former chief administrative officer Lincoln Saunders said the memorial was being treated with “sensitivity” because it was seen as “a tombstone for the mass burial.”

The memorial used to be behind the chain-link fence that surrounds the property. The changes the city made two years ago essentially cut out a corner of the fence, making the memorial publicly accessible and creating a seating area for anyone who wanted to visit it.

Under Virginia law, owners of private property that contains grave sites are required to grant access to descendants of the dead and anyone conducting genealogical research. The law specifies that landowners cannot put up walls or fences that would make access to graves impossible.

‘Sleeping their last sleep’

The confirmation of the mass grave could strengthen the view that the marker more closely resembles the memorials to Confederate dead that can be found in Hollywood Cemetery than Monument Avenue’s former statues of generals that fought on the side of preserving slavery.

Hollywood — which banned displays of Confederate flags in 2020 — is the burial site for thousands of Confederate soldiers and Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s first and only president. The cemetery contains a 90-foot tall granite pyramid dedicated in 1869 as a memorial to the enlisted men buried there.

In 1871, Richmond’s Daily Enquirer newspaper published an article that suggested moving the soldiers’ remains from Manchester to Hollywood Cemetery.

“Just on the suburbs of Manchester, and near Oakwood Park, are buried a large number of soldiers from different Southern States, who died at the South Carolina hospital, in this place, during the war,” the article read. “Will not some of our ladies select some good day, and place a few flowers on these little mounds, where sleeping their last sleep rest so many of the loved and lost chivalry of our sunny land. They can surely get some young men to aid them, and by next year we hope the Hollywood Association will have them moved.”

Before Manchester was part of the city of Richmond, it was an independent town and later, a city. The separate jurisdictions and tolls on the Mayo Bridge connecting Manchester to Richmond, the researchers wrote, made it “logical” for some Confederate dead to be buried at the relatively small site near Manchester’s wartime hospitals instead of being taken several miles to Hollywood or Oakwood cemeteries.

The surveyors seemed surprised to find “nearly perfectly straight rows” of burials, which they said are not typical in most cemeteries.

“This forensic data may suggest mass individual burials within trenches that span the length (W-E) of the lot (and likely outside the bounds),” wrote the Terrasearch team, which was led by David Givens, a VCU graduate who has done extensive archaeological work at Jamestown.

The report also pointed to the possibility of so-called “limb pits” deeper in the site containing bodies or “portions of bodies.” A decade ago, archaeologists excavated a limb pit discovered at Manassas National Battlefield Park to gain a better understanding of how combat surgeons amputated arms and legs during the war.

The firm hired by the city noted its methodology is not “foolproof.” Former roads on the property and a network of groundhog tunnels obscured some of the images. But the company was clear that its tally of 742 potential graves is most likely an undercount.

“While comprehensive, the 1857 Manchester Municipal Cemetery GPR survey does not likely represent all potential graves within the gridded survey area,” the report said. “Although many of the probable and possible interments exhibited relative clarity in the geophysical analysis, the density of the burial pattern within the cemetery made absolute identification of all burials nearly impossible.”

The city paid the company $8,500 to complete the survey of the site, according to officials.

'At this point, we're leaving it as is'

Mike Sarahan, a local resident who objected to the decision to spend thousands of public dollars on upgrading the memorial, said the report revealed a situation “so much bigger than anyone imagined.” It raises more questions, he said, such as what happened to the bodies beneath the facility the city built almost a century ago.

“My issue all along has been DPU’s misbegotten project to reposition and showcase the Confederate marker located on the substation property,” Sarahan said in an email. “It feels to me like we are at the start of what will be an extensive undertaking to deal with the complicated historical circumstance that has just unfolded.”

He added that he still believes the UDC marker should be removed and stored with the rest of the Confederate monuments Richmond took down.

“Mayor Stoney often claimed that all of the Confederate memorabilia had been removed,” Sarahan said. “That's not the case.”

Mira Signer, a spokesperson for Mayor Danny Avula, said there are currently no plans to remove the marker or make other changes to the property.

“At this point, we’re leaving it as is,” Signer said. “I think the mayor is not inclined to direct resources at this time toward moving the memorial or changing it. There’s tons of other pressing priorities.”

The city’s decision to install the bench a few years ago was driven in large part by Sean Withrow, who lives a few hours away in the town of Goshen and pushed for more access to the site out of respect for his fourth great-grandfather, Confederate private Thomas M. Ross of South Carolina.

Ross died at Manchester’s South Carolina Hospital in 1862, according to historical records included in the TerraSearch report. Those records don’t say exactly where the bodies of the dead were sent, but Withrow says his ancestor was among those who ended up in the burial ground.

“These graves are of people who have been lost and forgotten for 163 years,” he said in an email.

Hundred of graves, Withrow said, could mean “thousands” of people like him who might be searching for someone buried there.

Now that the city knows there are both Confederate soldiers and civilians buried on its property, Withrow said, the UDC marker should remain in place and the site should be turned into a proper cemetery “where people can visit the ones who made their lives possible.”

The Richmonder is powered by your donations. For just $9.99 a month, you can join the 1,000+ donors who are keeping quality local journalism alive in Richmond.

He said he recognizes others might disagree with his perspective. But to him, he said, sharing the same DNA with Ross across generations is reason enough to remember him and respect his “final resting place.”

“In the end of our lives, that is all any of us can hope for,” Withrow said. “To be remembered and not forgotten.”

Contact Reporter Graham Moomaw at gmoomaw@richmonder.org