Discovering history along the South Bank of the James River

Nancy Kraus wrote The James River Canal on the South Bank: A History and Pictorial Survey of the Canals, Westham Foundry and Railroads Around Richmond, Virginia, which is available now.

The search for understanding the history of the canals and canal-works on the south bank of the James River began serendipitously.

While investigating the landscape and historic resources in the Southside neighborhoods of Spring Hill, Woodland Heights and Forest Hill, several local residents raised questions about "the canal," a stone lock, an underwater wooden structure, and several other stone ruins. Puzzled and curious, I commenced what would become a decade-long adventure.

Along with a score of friends, we explored and photographed every visible clue from Manchester on the east to the Huguenot Flatwater Park on the west. We discovered multiple stone locks, stone dams and walls, spillways, culverts, an underwater head gate, and the stone and brick foundations of several buildings.

Because the canal-related resources are mostly situated within the boundaries of the City of Richmond’s James River Park system, they survived the expansive waves of 20th-century development in the greater Richmond area.

We realized that we had discovered the remains of the original James River Canal (1785-1796), which is one of the oldest transportation canals with locks and a towpath in the United States, the Manchester Canal (1819-1835), which is the oldest continuous canal in Virginia, the site of the Westham Foundry (1781-ca.1870), and relics of Virginia’s first two railroad lines — the Chesterfield Railroad (1831) and the Richmond & Danville Railroad (1848).

A slow process

Then as now, the wheels of progress turned slowly. All told, establishing functional water transport systems on the South Bank took more than 60 years.

Raising capital, both public and private; designing the pathways; obtaining rights-of-way; navigating governmental agencies to secure approvals; and finally gathering a workforce of mostly enslaved laborers to excavate manually a four-by-four ditch (with picks and shovels in a malaria-prone environment); blasting granite channels and sluices, a dangerous undertaking at best; and finally constructing locks and guard-gates to create a navigable system, all proved a daunting endeavor.

Floods and maintenance costs overwhelmed the James River Company’s financial resources, dooming the future prospects of the original James River Canal.

In February 1818, the Virginia Senate adopted a resolution charging that the James River Company had failed to perform according to their charter; that the attorney general was to institute proceedings against the company “for the purpose of ascertaining the truth,” and that the Board of Public Works was “to cause an accurate survey to be made of the James River and its branches, for the purpose of ascertaining the best means of improving the navigation thereof.”

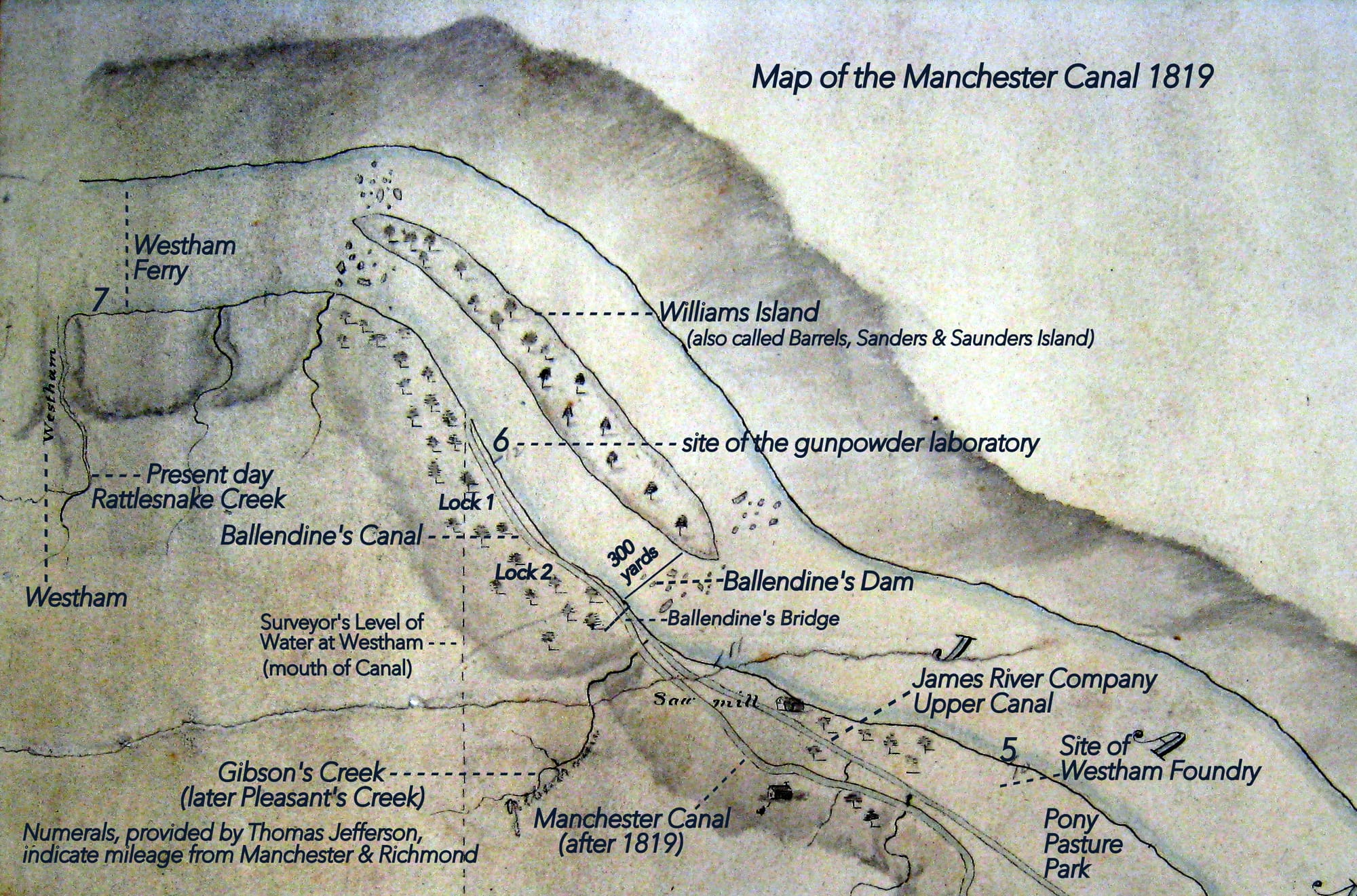

Hugh P. Taylor, an accomplished surveyor and engineer, charted the existing James River Canal and basin. Isaac Briggs and Thomas Moore, Surveyor and Engineer of the Commonwealth of Virginia, respectively, produced A Map of the Manchester Canal 1819.

One of the most geographically accurate maps of the south bank of the James River, the manuscript map illustrated the margin of the river between the “Level of Westham” on the west and the “Level of the surface of the River at the head of Tide-water” at the Manchester wharf. Executed in pencil and watercolor, the map is both a work of art and a directory of significant features in and around the Southside canals in the early 19th century that may be discovered even today.

Railroads take over

Although a group of Southside capitalists completed the Manchester Canal between the Town of Manchester and what is today the Huguenot Flatwater Park in 1835, their work was subsequently rendered obsolete.

Political operatives and investors on the North Bank, eager for their own financial gain, commenced the James River & Kanawha Canal by 1835, completing the continuous canal on Northside in 1851, another long and arduous slog. Both transportation canals, north and south of the James River, were upstaged in short order with the inauguration of Virginia’s first railroads, a progressive trend in transportation that spread like wildfire throughout the state and country.

The Chesterfield Railroad, Virginia’s first common carrier railroad, began operating between the Midlothian coal mines and the Manchester docks in 1831.

This gravity-powered railway offered cheaper, faster, and more dependable transportation than the canal. The Richmond & Danville Railroad (R&D), Virginia’s first steam operated railroad, was chartered in 1847. Initially the railway offered service between the coal pits in Chesterfield County and the Manchester ship-docks.

The R&D instituted freight and passenger service on the south side of the river in 1851, with trains operating six days a week. By the time the tracks were completed to Danville in 1856, flag stops and stations, including Rockfield Station below Forest Hill, dotted the 141-mile route. For the most part, the tracks of the Richmond & Danville Railroad were laid parallel to the towpath of the Manchester Canal, with spurs servicing various commercial enterprises.

Preserving history

A significant motivation for writing a pictorial history is to encourage recognition and preservation of the canal-related archaeological sites and structures that survive along the south bank of the James River. Both of the original locks, constructed between 1785 and 1789 by the James River Company for its Upper Canal, are extant. Recognizing the true history of the oldest James River canals may encourage stewardship and interpretation of the archaeological relics and stimulate future research into Richmond's rich transportation history.

The story of the archaeological sites and structures along the South Bank of the James River are truly reality hidden in plain sight.