‘Brilliant at the basics’: How one elementary school is beating the trends and boosting literacy rates

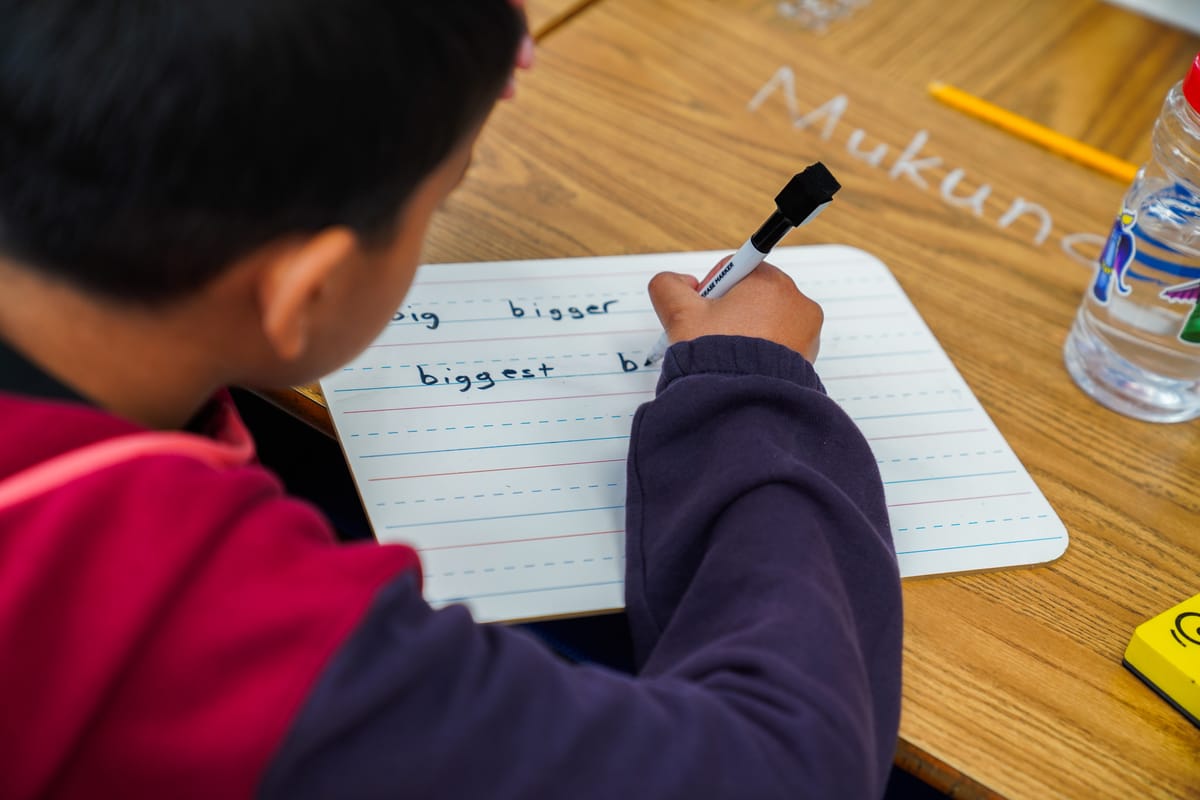

On a Tuesday morning in late March, Amira Boland is teaching her second grade class of about 20 students at Lois Harrison-Jones Elementary phonics – specifically, how to add suffixes “er” and “est” to the end of words with one vowel and ending with a consonant. The word on the board is “bad.”

“I want you to turn your buh, into an mmm,” the teacher tells the students, as they write on their dry erase boards and in notebooks. “Read your new word in three, two, one.”

“Mad,” the kids respond in unison, with one child singing the word into a high-key note.

Boland asks students to turn the new word into “madder,” and then into “maddest.”

“I already did that,” one student said, getting ahead of the teacher.

Boland said most of the students were at moderate risk of developing reading difficulties when they started second grade, a pivotal time, as studies show students who can’t read by third grade are at a disadvantage for the rest of their life. Now, with a recently adopted curriculum and hands-on support from staff, those students made a “ton of growth” by winter.

“I only had two students in that moderate risk band,” Boland said.

Boland and her students aren’t alone in that success. The trend is present within the entire school, as 85% of third grade students passed the Standards of Learning assessment last year, the second highest rate in the school division. That applies to disadvantaged students too, as the school had the largest percentage in the district of disadvantaged 3rd graders passing the assessment.

The reason for the school’s success is not a simple answer, and is due to multiple factors, including the division’s and state's focus on improving student literacy. They also attribute the increase to a recently implemented curriculum based on the science of reading, higher teacher retention, additional after-school programs, and better relationships between students and school staff.

“They don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” Principal Nicholas Lereche said. “When a teacher comes to them and says, ‘read this book,’ but there’s no relationship, the likelihood of it happening is slim to none. Whereas if there is a positive relationship, it increases the students’ drive and intrinsic motivation.”

A variety of reasons

Boland uses UFLI Foundations, a reading instruction curriculum developed by the University of Florida Literacy Institute. The curriculum is designed for students in kindergarten to second grade and can be used in any grade.

Lois Harrison-Jones was one of the earlier schools within Richmond Public Schools that piloted UFLI Foundations last year and noticed its success, Lereche said.

A year later, Richmond Public Schools adopted the curriculum into all schools.

“UFLI was just a one-hit wonder,” Lereche said.

Teacher retention also increased at the school, which Lereche attributed to the improved screener and SOL scores. The school had a 50% turnover rate of teachers in previous years, Lereche said. There are 20 classroom teachers, and it can be difficult building on skills with new teachers.

“You’re starting back at square one,” he said.

Eighty-eight percent of teachers remained at the school last year, which Patrick McHugh said is a big feat for the school. The father of three and president of the school’s PTA said that the increased retention is as a result of an invested PTA and better leadership.

“We took it as seriously as we could this year,” he said.

The PTA provided more after-school programs by paying teachers extra for staying after school hours. Part of the money came from sales from the PTA’s annual book festivals. McHugh said that teachers stepping up has led to the expansion of clubs that allow students to use reading skills, like the comic book and bird watching clubs. Lereche said it also furthers a bonding relationship between students and teachers.

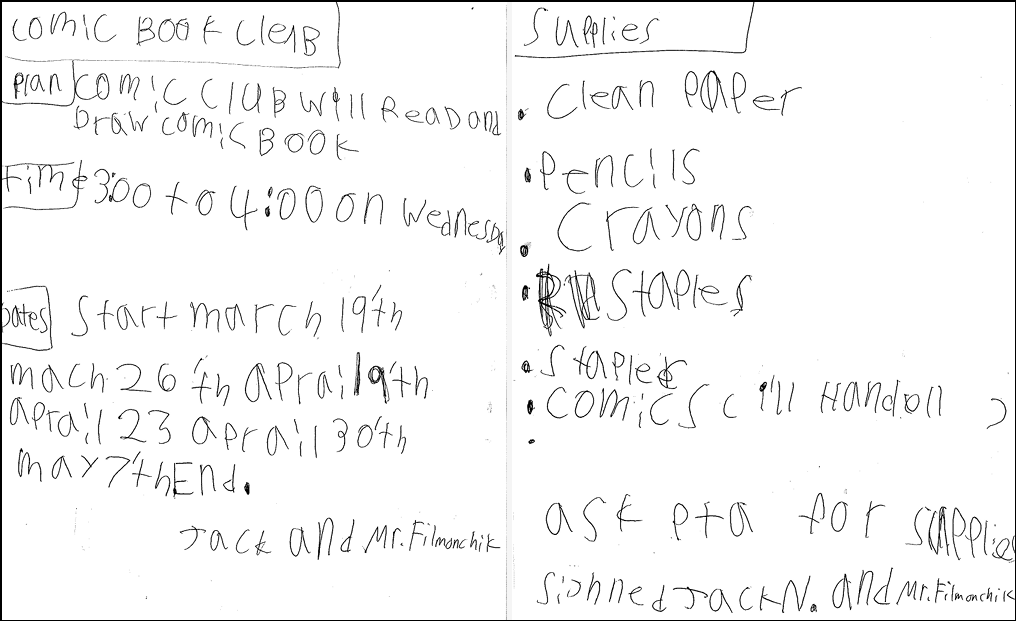

Brittany Nonnenmann’s son, second grader Jackson, is the creator of the comic book club at the school. Nonnenmann said that Jackson always loved reading books – specifically comics like the Captain Underpants series – and created about 20 of his own. He suddenly had the idea to bring his love for comic books into school by creating an after school program for it, which he first brought to his mother.

“He participated in a bunch of after school clubs and he said, ‘Mommy, I think I want to make a comic club,’” she recounted. “So he went to school, he talked to some of his friends who he knew really liked comics … and he drummed up excitement about it.”

He soon got to work, with the support of Mr. Filmonchik, a first grade teacher. In his proposal, he wrote that the club will meet on Wednesdays from 3 p.m. to 4 p.m., starting on March 19 this year, and require supplies like paper, pencils, crayons, and staples, before signing his name at the bottom. It was approved by the PTA soon after.

Nonnenmann said that in addition to the support he gets from home, the teachers at school foster his love for comics, and didn’t shun his idea.

“There was never a moment throughout when he was trying to drum this up that any teacher or any staff was like no,” she said.

She said that his inspiration to do so came from the fact that students “feel comfortable with their teachers and staff, and that the staff and teachers have support from parents.”

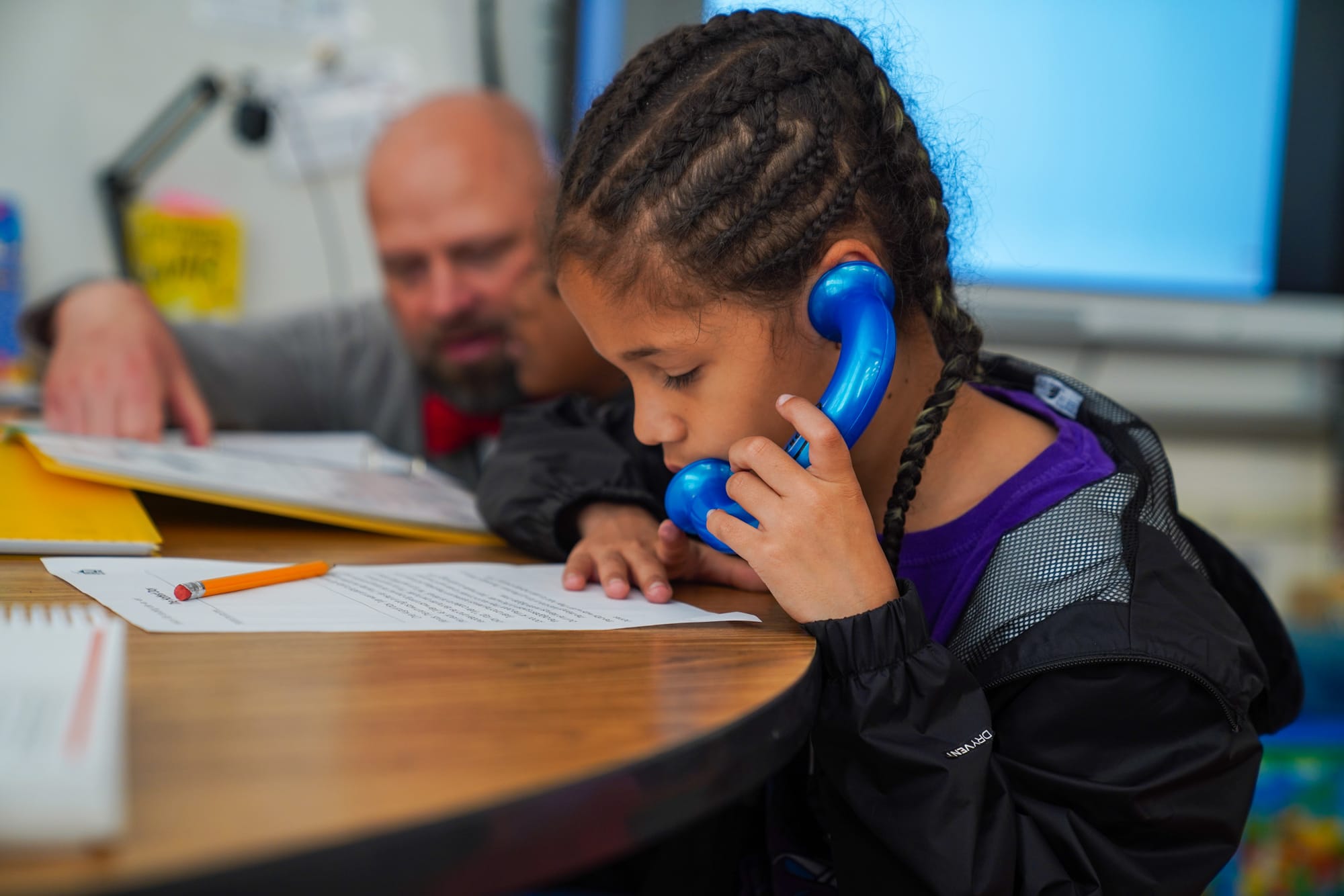

School officials also said the division’s and state’s focus on literacy allowed students to grow. Robin Majer, a reading interventionist for the school, said RPS implemented a reading intervention program about five years ago where she is given a 45-minute block to work independently with three to four students lagging behind in reading proficiency.

“That has been huge in helping our students who are having the most trouble reading catch up gradually,” she said.

The state passed the Virginia Literacy Act in 2022, mandating scientific research and evidence-based literacy instruction, intervention, screeners, and literacy plans in all schools to improve literacy outcomes for young students.

“The Virginia Literacy Act kind of turned everything on its head,” Lereche said. “Instead of doing it, ‘because this is how we’ve always done it,’ the Virginia Literacy Act made you look at what you were doing. And it had to be rooted in evidence.”

Elie Caples, a first grade teacher at the school, said that the combination of the UFLI Foundations curriculum and good leadership helped her as a teacher and aided students across the board.

“One of the best things about teaching first grade is that you get to see their world just open up,” she said. “They’re like, ‘I can read this!’”

Parents laud school’s approach

While her son, Roan, was attending Kindergarten at a private school, Megan Jones noticed he needed additional support that the school was not providing. He knew how to read, but it was “slow and patchy.”

She enrolled him into the first grade at Lois Harrison-Jones Elementary this year, and she immediately noticed improvements within the first three weeks.

“Now he’s reading at a level that is way higher than he’s supposed to,” she said. “It’s just absolutely blown up all the way, and not only that but he’s getting the support he needs.”

Jones said Roan now reads chapter books with up to 150 pages without help.

By winter this year, nearly 78% of Lois Harrison-Jones students were not at high risk of developing reading difficulties, an 8% improvement over the fall, according to results from the Virginia Language and Literacy Screening System. This is a trend seen throughout all schools in the division.

McHugh is impressed by the school’s efforts in increasing literacy proficiency. His children have always been bookworms, but the school brought it out of them more, he said. He remembers when he caught his daughter Irelyn, a second grader in Boland’s class, laughing while reading a book.

“She had fallen into the book,” he said. “She was in the book rather than just reading word after word.”

Caitlin Bojarski said that when her son, Michael, was in kindergarten he was initially unable to read words that were six letters or more long. The instruction mainly consisted of “sight words,” words that students can easily read just by looking at them. Anything outside of that just “didn’t really click with him,” she said.

She said It finally did after the school introduced UFLI Foundations in the middle of first grade.

“It just made such a difference,” she said. “We’re driving along and he’s reading signs. We’re going to restaurants, he wants to read the menu himself.”

Michael, who is now in Boland’s second grade class, doesn’t get discouraged by big words, and works on sounding it out until he gets it, she said.

McHugh said that ultimately the solution to getting schools to excel academically is not “complex.”

“Brilliant at the basics,” he said. “It is being really good at the basics of what we do, as teachers, as a community.”